'What is it that David Chipperfield uniquely does? … He does architecture better than any of his contemporaries'

On his death bed, Reyner Banham, our finest critic, made one last attempt to understand architecture. There is a marked difference, he said, between the ‘good design’ of Christopher Wren and the ‘absolute architecture’ of John Soane. ‘What is it that architects uniquely do?’ he asked, wary that the discipline was a black box quandary, recognised only by its output but with contents unknown. ‘The answer, alas, is they do architecture, and we are thus back at the black box with which we began.’

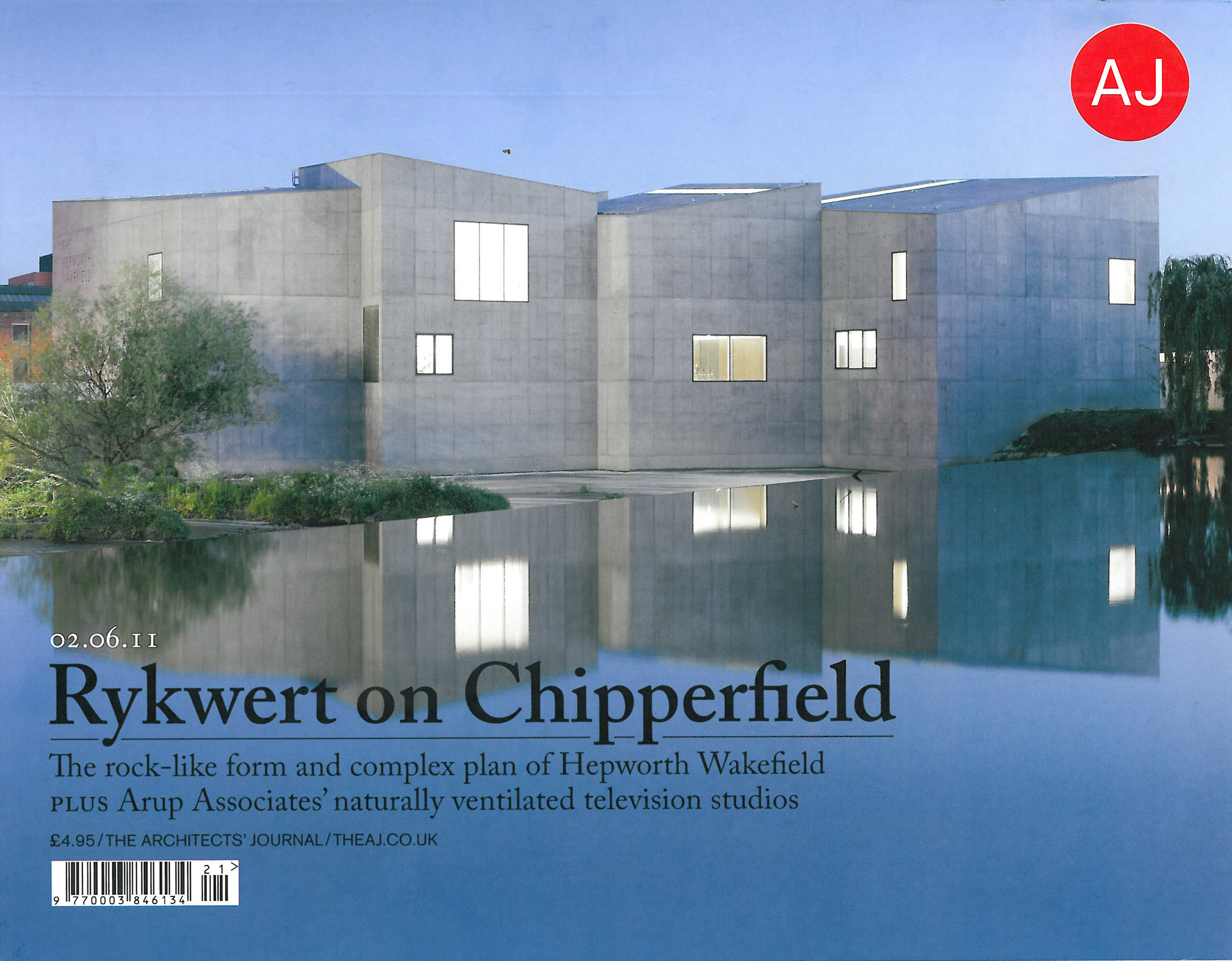

What is it that David Chipperfield uniquely does? The answer to that is quite simple. He does architecture better than any of his contemporaries. The 2007 competition-winning extension to Museum Folkwang is his fifth German building to be shortlisted for the Stirling Prize. It is a classic ‘black box’ building: you can sense the presence of architecture in Folkwang, as powerfully as you feel its absence, say, in Manchester’s Trafford Centre or in south London’s Strata.

Yet photographs cannot convey its magical charm - its architecture - and I’m not sure that words can, either. You might just have to go there to see and feel what I mean for yourself.

We know what Banham meant when he wrote that we can recognise the presence of architecture, that specific mode of designing buildings that very few architects actually employ, ‘in the bottom of Philip Johnson’s AT&T building, for example, but not in its middle or its top’, or in the lanterns of the mausoleum at Soane’s Dulwich Picture Gallery. We might not know exactly what it is, but we can sense when it is there. In Folkwang that sense, that quality, is with you all the time.

Banham was not being rude about buildings that do not fit with his mirage-like sense of what architecture is. There are many other modes available when it comes to making buildings and there are many things to appreciate in those kinds of buildings, too. But they don’t have ‘whatever it was that Hawksmoor had done to make great architecture out of as humdrum a concept as the interior of St Mary Woolnoth’.

Wandering through the extensive reception hall of Folkwang and along its broad corridors arranged around courtyards and with floor-to-ceiling windows, that feeling of difference, a feeling you don’t get in bsf schools, no matter how well designed - a mysterious, blissful charm - is intense. Good design per se is not necessarily architecture, Banham argued, and, post-Essen, I can see his point.

Folkwang has all the hallmarks of good design: it is structurally efficient and has beauty of form; it is functionally clear and spatially deft; it is environmentally sound and ‘honest’ in its use of materials. Others on the Stirling Prize shortlist have these qualities as well - the Angel building and the Velodrome, for examples, tick those boxes too. But neither mesmerises quite like Folkwang.

They are simply not as architectural as Chipperfield’s museum. Folkwang has something else in the mix. The spell cast by Folkwang is undoubtedly strengthened by what is contained within: a great collection of modern art - Van Goghs, Cézannes, Pollocks, Gurskys, the list goes on. Even after the Nazis scattered its ‘degenerate’ collection, today’s museum remains one of Europe’s best.

At Folkwang, architecture, though clearly all around, is very much in the service of the art. It is the antidote to all those galleries and museums commissioned in the past decade on the basis of how they will look, but which do little for the content within.

Chipperfield’s big idea at Folkwang was to spread the public spaces of the building across one floor, flattening out the four-metre drop that runs across the site. ‘It is as if it has always been this way,’ said Britain’s German ambassador, Georg Boomgaarden, when the building reopened in January last year.

You can see the definitive idea clearly in the sketch Chipperfield made early in the process, which extends the courtyard arrangement of the original and marks out wide corridors and rectilinear galleries. Scratchy and in pencil, it resembles a magical symbol of sorts, a spell - or icon - loaded with meaning and intent.

And, if we were ever to prise open Banham’s black box, wherein lies the essence of this mysterious thing called architecture, it might well be empty, save for this fuzzy little drawing of Museum Folkwang.

Q+A with Alexander Schwarz, Design Director, David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

AJ. How would you describe your design concept for the project?

AS. The different parts of the museum were grouped into compact volumes, due to their special daylight requirements. All public areas are situated on one floor created by a plinth, reacting to the slope of the site. The parts are organised around courtyards with trees. These courtyards connect the museum to the outside, to the existing building, and to the city.

AJ.What was your approach with regards to the existing building?

AS.We borrowed generic qualities, such as the datum of the publicly accessible floor, the circulation around courtyards, the directness of daylight and its general tranquility. We tried to formulate these qualities more explicitly, with the aim that the complex would be read as a whole. Although the new section is an extension, it is three times the size of the existing building and, furthermore, provides the main entrance to the museum.

AJ. What lessons from previous schemes did you bring to the project?

AS. As the Museum’s collection is so extraordinary, the role of the architecture should be to provide an appropriate setting. It should define the proportion of accessibility and protection as well as the proportion between floor, wall and daylight. This does not mean that the architecture itself becomes neutral. The character of the building adds to the individual experience of the collection.

AJ. How are museums evolving as a typology?

AS. They are essential public spaces, since they and their original objects cannot be globally experienced, but only at specific locations. They provide spaces where the individual can reflect and re-examine what may be known differently through the media. This is a crucial quality of museums. In the future this quality may be more interesting and essential for the typology than attracting attention through sensational architecture.

AJ. Where does this building sit in the evolution of the practice?

AS. Museum buildings represent one of the focuses of the practice’s work. Folkwang states a clear position of what a museum for an important collection can be within the body of our work.

AJ. Could this scheme have been delivered within the same timescale and with the same attention to detail in the UK?

AS. It was a challenge in Germany. It would be a challenge in the UK and elsewhere.

AJ. You have already won the Stirling Prize and been nominated seven times - does winning still matter?

AS. The Stirling Prize is about recognising good buildings. It is always rewarding if a project is shortlisted, whether it wins or not.