'David Chipperfield’s bold, striking and singular Hepworth Wakefield gallery will win the favour of the public.'

Since Wakefield was thoroughly Thatcherised some 30 or 40 years ago – its coal mines shut down, its textile industry squeezed out of existence – it is just as well that its most distinguished (and certainly most famous) native was a sculptor: Barbara Hepworth.

She was a pioneering figure, a contemporary of Henry Moore, John Piper and Ben Nicholson (whom she married) and is not commemorated in her city by a monument or statue – that would have been unseemly – but by a gallery centred on a rich collection of her work, presented by her family. At its core are many of Hepworth’s prototypes and full-size plaster mock-ups of stone and bronze sculptures, her models and her archive – even some of her working tackle – to rival the display in her other home at St Ives, in Cornwall.

A context is provided by some excellent work by her contemporaries, on loan from other national collections. The gallery, which opened last Saturday, will also have ample space for visiting shows, and has already begun to commission work from younger artists. It also holds valuable records and studies of local antiquities. With the Leeds Art Gallery and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, it will focus attention on the worldwide impact of 20th-century British sculpture.

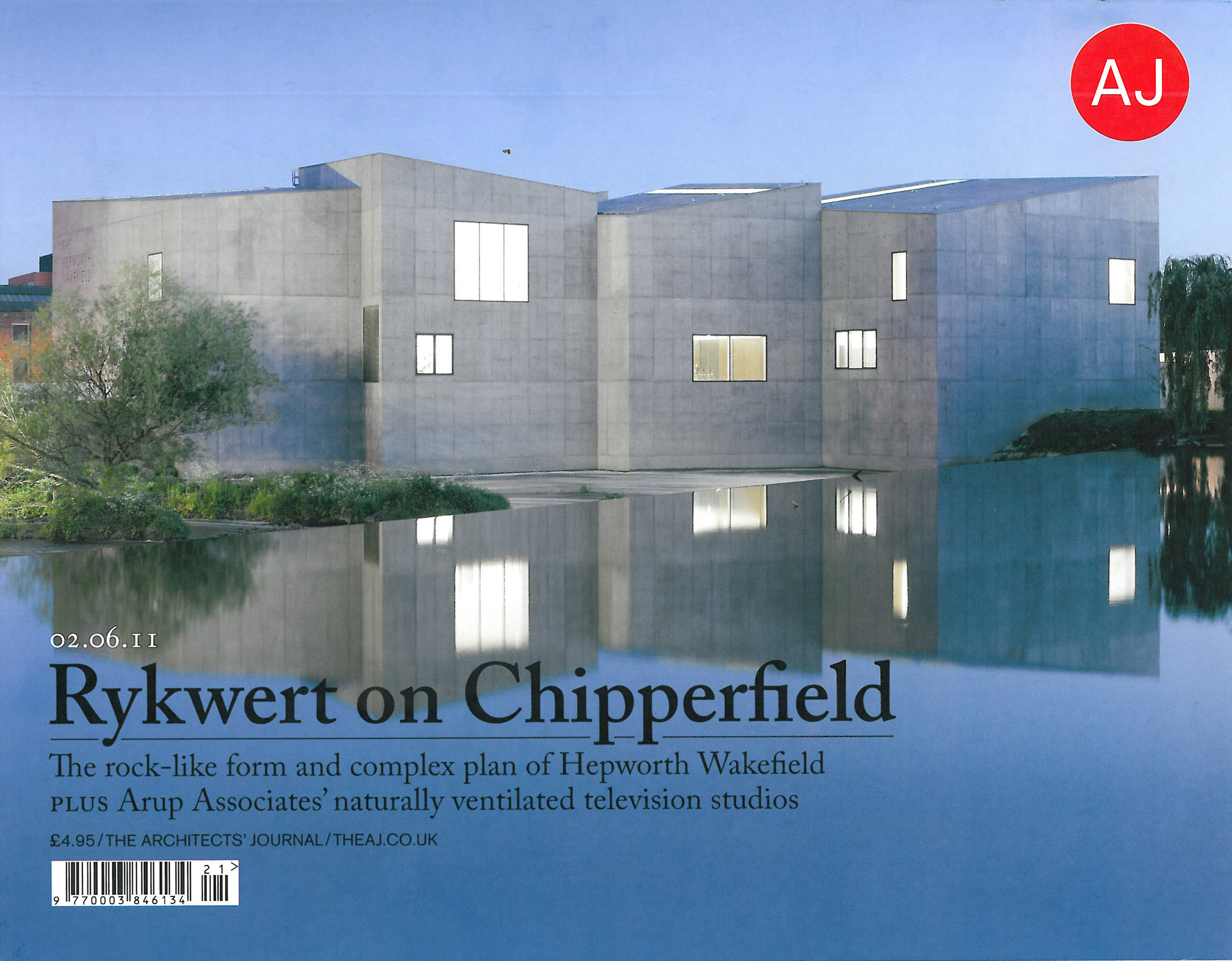

The site chosen for the new museum is pivotal, outlined as it is by a bend of the river Calder, where it makes a headland, overlooking a weir. To the east, this part of the town is bordered by the Calder and Hebble navigation locks, part of the canal network developed in the 18th century. Several fine 18th and 19th-century warehouses nearby recall the town’s importance as a link in river and canal transport routes. Some of these are being reinstated and there are ambitious plans to redevelop this part of Wakefield.

The site is also overlooked by two bridges: a harsh modern motorway filter beside a 14th-century stone one with a chantry chapel, one of Wakefield’s salient monuments. The chapel’s once picturesquely ruined charm was restored out of it by George Gilbert Scott in the mid-19th century, though it was painted before that by JMW Turner, whose watercolour can be seen in a room from which the bridge itself is also visible. The gallery site was for some time vacant and inaccessible, so the opening of the Hepworth Wakefield is bound to transform the whole topography of this district.

To the casual observer, the building may at first appear almost as a geological formation, a rock-like, random assembly of variegated blocks. That studied casualness is an essential element of the composition. Neither programme nor site imposed a large, unified building, but rather suggested an episodic approach. Various groupings, some more, some less fragmented – were tried.

However, the 10 pavilions of the adopted plan seem so right in scale, and sit so well on the site, that, in hindsight, it is surprising that Chipperfield did not favour it from the beginning. That configuration results in a building that has no obvious nor dominant facade, yet it hugs the water’s edge and relates critically, in scale, to the industrial buildings which surround it. The situation over the weir allows the walls to drop sheerly down to the water, but also, inevitably, required flood protection, so that the sheet piling on which the walls rest benefits the whole site.

From the town centre, the Hepworth Wakefield is entered from the west over a new footbridge across the Calder, thrown at right angles to the weir, which allows the visitor sheltered access through a forecourt (also outlined by a small existing listed building) onto which the café opens. Such southward exposure may not always work elsewhere, but seems permissible in Yorkshire.

The whole ground floor is taken up by the extras of a modern museum: reception, café and shop, lecture (‘performance’) hall, study rooms, conservation labs, picture store, loading bay and offices, while the services are confined to the basement or contained inside the hollow walls.

The trapezoidal galleries, each a different shape and size, take up the upper floor. They all have clear roofs pitched on their long axes, and receive much of their light through skylights positioned parallel to the highest wall of each room. They are partially screened by a projecting ceiling, and so controlled by louvres that daylight filters down the walls like a graded wash, but never affects any exhibit directly. Six of the 10 galleries also have a picture window, so that the visitor is at no point isolated from the drama of the surroundings and has a clear view of the play of the waters of the weir.

A cursory look at the plan shows that the studied randomness of the 10 galleries is cunningly organised around two straight walls, which meet at right angles to the entrance hall at ground level. These orthogonals are not allowed to dominate, however: they are internal to the building, and one is even suppressed on the gallery floor, while the pavilions fan out from them.

A closer look at the plan reveals that they are organised on complementary 78/12, 5/85 degree alignments, which appear together in some spaces, notably the ‘performance’ room. The structural outer skin of those interior spaces is what you see outside as a grouping of solids. Within, none of the rooms are aligned en suite, but a visitor passes from one to another obliquely, allowing museum and exhibition curators to group sculptures and paintings so as to guide the visitor by a choice of works that will create its own path.

That strikingly geological first impression of the building is enhanced by its outer construction of load-bearing, self-compacting and pigmented concrete, cast in-situ to give a smooth finish. The roofs are spanned by steel trusses and covered in precast concrete slabs, grouted to the same colour as the walls.

This enhances the geological quality, which gives the building a singular character, all the more arresting in that it does not look like most of Chipperfield’s recent buildings. In fact, the original project dates from 2003, when he won the competition; it then went through several transformations and the building that was inaugurated last Saturday seems not only assured and mature, but also happily wedded to the site.

The purple-grey tint of the concrete emphasises the lithic look and has invited comment, not always friendly, from the public, (the contractors called it ‘Hepworth Brown’, or so it is said), as any striking new building inevitably does. But I am prepared to bet that, within very few years, if not months, it will be looked on with pride and affection.