'After decades of success abroad, David Chipperfield is at last winning recognition at home. With two major galleries opening this spring – his first public works in Britain – he tells our critic why he values substance above spectacle.'

David Chipperfield doesn't fly helicopters. He did not rise from poverty to incredible wealth. He is not famous for flaming rages. He does not design buildings with wild angles, or gravity-defying stunts, or resemblances to fruit, vegetables or household objects. He does not wear Miyake capes, doesn't invite Brad Pitt into his office, and has never been on Oprah. He makes no claims that his work represents the anguish of history, or the dynamic future, or that it will, through sustainability, save the world. In short, he lacks the accoutrements that make some other architects – let's say Foster, Libeskind, Gehry or Hadid – celebrities.

Instead he is English, 57 years old, and has nothing more exotic than a slight West Country burr. He sails small boats a bit, and lives in a pleasant, well-lit central London apartment amid things of culture: a cello, a saxophone, books and DVDs in several languages, objects given by Italian designer friends, some unusual ceramics and mementoes of his children's early years. Many of these are kept in big glass vitrines that form the walls between rooms, forming a personal museum.

For decades, he has proved himself abroad. He is much sought-after for projects that help define cities' modern views of themselves, often in relation to rich or fraught history. He has built Barcelona's law courts, extended Venice's cemetery island, and rebuilt the bombed-out Neues Museum in Berlin, a project with many raw nerves waiting to be touched. He has also helped enhance the identity of cities with less deep roots, with a museum in Anchorage, Alaska, and a library in Des Moines, Iowa. He deals in dignity, in gravitas, in memory and in art.

Until recently British towns proved resistant to him. This year, due to some inexplicable shift in the weather, everything has changed. He has designed two new public galleries, in Margate and Wakefield, which are opening in April and May. He is working on a large development next to Waterloo Station, another near Buckingham Palace, and a residential block in Kensington. He is designing private houses of stupendous but well-tempered poshness in Kensington and Oxfordshire. Next week, as if to consecrate his acceptance by his homeland, he receives the Royal Gold Medal, the country's highest architecture award.

Chipperfield talks insistently and passionately about architecture, about the things that, in his view, actually matter in the design of buildings, and the things that don't. He likes ‘permanence’, ‘substance’ and ‘meaning’, and dislikes designs that are spectacular for the hell of it. ‘I don't think architecture is radical,’ he says. ‘How can something that takes years and costs millions be radical?’ He is generally too diplomatic to name names and when he does mention one, Zaha Hadid's, he is careful to praise her ‘real genius’, but it is clear that her buildings are among those he has in mind when he criticises the ‘application of genius willy-nilly’.

He thinks that architecture now tends to alternate between self-indulgent fireworks and acting as a tool of developers. ‘Architecture has curled up in a ball and it's about itself,’ he says. ‘It has found itself either as a freakshow, where you're not sure if it's good or bad but at least it's interesting, or at the behest of forces of commerce.’ On the one hand, famous architects design exotic-looking museums and towers that hog the attention of the media. On the other, large pieces of city get built without discussion. He cites Paddington Basin, a big development in west London. ‘Where the hell did that come from? It's just a potato field, just a crop. Its individual buildings might be perfectly good, but shouldn't there be some bigger concept about what it gives to the city, rather than just development?’

Chipperfield likes to compare Germany, the country most congenial to his public-minded seriousness, with Britain. Germany gave him ‘the experience of a lifetime’ in his rebuilding of the Neues Museum in Berlin. Britain gave him BBC Scotland's headquarters in Glasgow, where he was appointed amid grandiose claims about the BBC's Medici-like patronage of architecture, only to be pushed to the side in favour of ‘executive architects’ and see a coarsened version of his design built.

At the Neues Museum Chipperfield took on a grand 19th-century building, much damaged by wartime bombing and then by neglect under the old East German regime, and returned it to its original purpose as the home of ancient treasures including the bust of Nefertiti. His big idea was not to create a perfect simulacrum of the prewar building, nor to juxtapose the wreck with something crystalline and perfect, but to create a fusion of original building, ruin and new work. In places rooms were restored to their prewar state, but more often they were cleaned up, stabilised versions of the spaces as he found them, with fragments of decoration clinging to exposed brick and stone. In places the pockmarks of shrapnel and the scorches of fire were left on view. Where necessary wholly new structures were built, echoing but not copying the old.

Here spaces are made by different layers of time: the making of the original building and its subsequent alterations, the bombing and decay, the restoration, the archaeological time of the exhibits and the faster-moving time of the daily visitors. It took 12 years to make, from Chipperfield's appointment in 1997 to its public opening the autumn before last, years of patient consideration of each fragment and bit of wall, of diplomacy and battles, of dealing with controversy. ‘The difference between good and bad architecture is the time you spend on it,’ he says, and here he got to spend plenty.

There was a move to get Unesco to describe the museum and its surroundings as ‘endangered’ because of Chipperfield's approach, and he was publicly accused of fetishising destruction, of harping morbidly on the horrors of the 1940s. He argued that his aim was not ‘demonstration of damage but demonstration of the beauty that was there’. The project eventually opened to almost universal acclaim, and Chancellor Angela Merkel, who had previously been cagey, declared it ‘one of the most important museum buildings in European cultural history.’ Berliners queued for three hours to see it on its opening weekend, and it has attracted 1.4 million visitors in the 15 months since its opening.

Chipperfield says that he was nervous about taking on the project: ‘I thought I'd spend 10 years on restoration.’ His wife Evelyn asked him if he was sure he wanted to do it. ‘She thought I'd do a lot of work and just end up with an old building that had been there before.’ Now, he says, ‘to have done something that means so much, a national object dealing with national emotions: nothing can compete with that.’

In Germany, says Chipperfield, there's ‘an idea that a city should be held together by something; there's an idea of what a city should be like.’ This something is a matter of public debate, in which ‘people feel they have the right to comment’. In such a debate an architect is ‘expected to be an intellectual leader’, but also has to work hard to articulate his or her position. Sometimes plans are put to referendum. ‘It can be frustrating,’ says Chipperfield, ‘but when people show an emotional attachment to some part of a city you can't be upset.’

He says that in Britain ‘people get up in arms when something is near their house’ but are less concerned about cities as a whole. ‘There is no discussion of the shape or form of a city in our planning system’ and architects are seen purely as ‘service providers’ for commercial clients, not as people with a wider duty to society. There's a reluctance to explain cultural work on its own terms. Rather things like museums are justified in terms of regeneration, in other words their supposed economic effect. ‘I'm uncomfortable with this,’ says Chipperfield. ‘It loads a building with responsibilities and expectations which are unfair. You should build a museum because you want a museum.’

If an architect tries to express ideas, ‘you're a ponce, arrogant’. Sometimes, when Chipperfield is debating with British clients, he finds himself thinking ‘hang on, I'm doing this for you guys. I'm trying to make it good. Why am I regarded as an awkward and quirky cog in this process?’

It's clear which of the two countries suits him better, but he tries not to portray them in black and white. Of Berlin he says it's easier to be high-minded about development ‘when you don't have much of it’. You could argue, he says, ‘that London has been very successful doing things its way. It has amazing energy and vitality.’ And, finally, clients in Britain are beginning to appreciate him, especially with the two galleries opening in the spring.

One is the Turner Contemporary in Margate, the town where Britain's greatest painter went as a refuge from London, and where the coast inspired many of his greatest seascapes. On a prominent site on the waterfront, there will be temporary exhibitions accompanied by loans of Turner paintings from the Tate.

Here Chipperfield is following a romantic, ambitious, but disastrous attempt to realise a shell-like object placed in the sea, by the Norwegian architects Snøhetta. This ended in lawsuits, eventually settled out of court with a payment to Kent county council.

‘The client was shell-shocked, literally,’ says Chipperfield, ‘and had less money than they'd started with,’ so he has responded with ‘a very secure and wholesome building’. It is simple, studio-like, almost shed-like, but still with a robust presence on the waterfront. Most of the designers' energy went into capturing the exceptional daylight on the Kent coast, which Turner described as ‘the loveliest in all Europe,’ and taking it indoors. ‘The light inside is fantastic’ says Chipperfield, ‘it is the best we've done and the best I've seen anywhere for a long time.’

The other is the £35m Hepworth gallery in Wakefield. Its highlights include 40 sculptures by Barbara Hepworth, who was born in the city, and works by her contemporaries including Mondrian, Giacometti and Ben Nicholson. It is the sort of unexpected treasury that crops up in British regional cities, where the legacy of industrial wealth funded flurries of artistic patronage, before it disappeared. The gallery is also big, at over 5,000 sq metres. It is being promoted as the largest purpose-built exhibition space outside London.

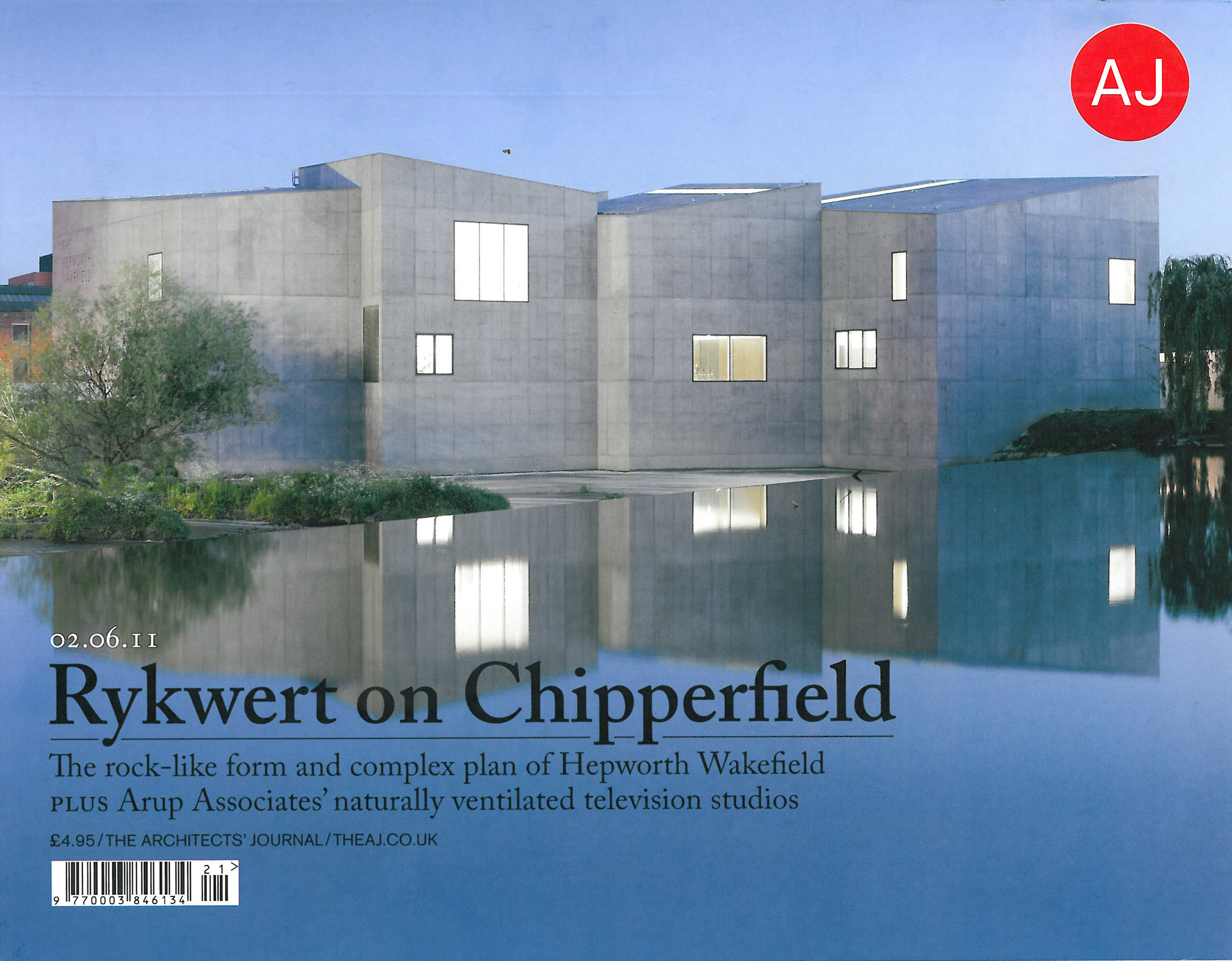

The Wakefield gallery consists of an irregular grouping of 10 pavilions, sited on a bend in the River Calder, with angled roofs that echo surrounding industrial heritage. The pavilions are fused into a somewhat sombre whole within which luminous interiors open up. As in most of Chipperfield's galleries, the art's the thing, along with the daylight that serves it. The exhibition spaces vary in scale to suit the different exhibits, with carefully modulated light from above and the side. ‘Artists and museum people think it's fantastic,’ says Chipperfield, but he is as yet unsure as to the local population's response. ‘The test will be whether the body of Wakefield receives this transplant.’

What all these projects have in common is the desire to bring out the best in the things that Chipperfield finds in the brief or site: the ruins in Berlin, the light in Margate, the art in Wakefield. To this could be added the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany, where a great collection of mostly 20th-century art is displayed in a deceptively simple-looking building. Here, he says, the ‘most important decision was to put all the galleries on one level. It is the most democratic and comfortable way of looking at art, and makes it a really nice museum to be in. No one knows why they enjoy being there, and there's no reason why they should. But it gives me satisfaction.’

This is not to say that his buildings are shy and retiring. They tend to have a strong presence, with right angles and straight lines predominant. He likes solid masonry and concrete, where you can see the stuff that is holding a building up, and sense its mass. In this he deliberately opposes the way that the modern construction industry likes to build things, which is to assemble factory-made pieces into flimsy-looking structures. He adheres, arguably too much, to the classical idea that architecture is about naked materials and structure seen in daylight. Mobility, surface, illusion, or the way artificial lighting forms cities at night, are less important to him.

He likes the appearance and reality of permanence, and is sceptical about architects' common fantasy that buildings can be as light and transient as aeroplanes or tents. ‘You always have to dig a hole in the ground and pour a lot of concrete into it,’ he says. ‘How much does your building really weigh, Mr Foster?’ he asks, in reference to the hagiographic feature film just released about Norman Foster, which celebrates among other things the lightness of his buildings. ‘If I thought architecture was nomadic and light-footed I'd be very interested, but it's not true.’

He stresses the less glamorous questions, such as ‘how a building's going to look five or 10 years later. How you do things is profoundly important. The quality of the Neues Museum's construction is extraordinary even by German standards, and people can smell that quality. The concept would not have been so convincing without it.’

He opposes the idea that architects are divided into chaotic geniuses who can barely hold their offices together, and the boringly efficient and commercial. He wants to run a business that ‘pays its staff, has a good time, and enjoys its work’. He is fundamentally self-confident and assured of what he is doing, and is not shy of saying when he thinks he has done something well, but he claims to be ‘very self-conscious that our work is boring. I feel very unoriginal… One feels like a dinosaur sometimes.’

He is not the most ingratiating of architects, and some of his buildings make themselves targets of the Prince Charles school of abusive epithets. You might, if you weren't looking very hard, say the green-glass boxes of the Folkwang look like a cold store, and his giant complex of law courts in Barcelona are uncomfortably prison-like, as if defendants were guilty until proven innocent. I can see someone coming up with the word ‘bunker’ in relation to the grey concrete of the Hepworth. Yet he talks to a surprising degree about engaging the public. He likes the way, when he was designing a museum in the seemingly unpromising territory of Anchorage, there were 10 public meetings, with the chance to hear what people did and did not like, and to explain what he was doing.

‘When your ideas are robust,’ he says ‘and when you're not playing games, it's not that difficult to explain. If it's fantastic to be in a place, or gives a particular experience, people get it. Professionals can make it more complicated than it needs to be. They have to be careful not to get too sulky about parts of a project that are in the end self-indulgent.’ He describes a shopping mall he's completing in Vienna; the owner, without any specialist knowledge of architecture, loves it. ‘It's just a department store with big windows and beautiful stone walls. That's all.’

David Chipperfield is an architect who reads books. For him a building is never enough on its own, but is always part of a wider culture. At the same time he talks in close detail about the stuff of his art. This combination is rarer than you'd think, and it is to be hoped that it survives his acceptance in Britain. Often it is a condition of recognition here that architects leave their most difficult ideas at Customs. The challenge for Chipperfield is to make sure it doesn't happen to him.