The experience of eleven years spent working on the rebuilding of the Neues Museum in Berlin, and more recently the refurbishment of Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie while at the same time contemplating how best to tame the endless sprawl of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has given David Chipperfield more insight into the deeper issues of museum culture than most architects ever acquire. These projects have been opportunities for him to think long and hard about what museums mean, how they work, what possibilities they offer artists and curators, and to explore the minds of the distinguished architects in whose steps he has followed.

The experience of eleven years spent working on the rebuilding of the Neues Museum in Berlin, and more recently the refurbishment of Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie while at the same time contemplating how best to tame the endless sprawl of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has given David Chipperfield more insight into the deeper issues of museum culture than most architects ever acquire. These projects have been opportunities for him to think long and hard about what museums mean, how they work, what possibilities they offer artists and curators, and to explore the minds of the distinguished architects in whose steps he has followed.

Architectural historians have tended to treat the museum as a single typology, one that is rooted in classicism. It is a type that emerged following Napoleon’s creation of the first imperial museum initially named for himself at the Louvre, at a point somewhere between Robert Smirke’s British Museum in London and Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Altes Museum in Berlin. A colonnade, with or without a pediment, a central entrance hall, and a sequence of enfilade rooms, mostly sitting on a basement store room level, have shaped the plans and elevations of museums all around the world. In many countries, the pictogram used to represent museums on motorways and street signs is still a pediment sitting on a set of columns. Now that Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim, and Jean Nouvel’s National Museum of Qatar have become more common as models for new museums than Doric temples, this sign, like the archaic outline of steam engine used to warn against railway trains, is what is called a skeuomorph.

In fact the museum is far from a single architectural category. Some museums are dedicated to individual collectors, others are based on individual artists. Some are about teaching, and shaping culture. There are many museums that are based on the psychology of individuals looking for immortality through a collection that can function as a mausoleum. Others are about nation building and the creation of a semi sacred place in which to display foundation myths. Some use urban renewal as an alibi for cultural provision, others try to boost the income and influence of older museums franchising their names. In his career to date, Chipperfield has covered most of these categories.

Rather than looking at every museum through the filter of a model created by Smirke, Schinkel and their successors for a very particular set of circumstances, there is much to be gained from understanding museum architecture through distinct individual categories. It is also helpful to understand where an architectural project fits into the individual history of an institution. Museums go through cycles of growth and decline followed by renewal. They make the architect face very different issues, depending on the stage at which they become involved. Architects can help with the creation of the identity of a completely new institution, working with a founding generation. Equally they are asked to adapt and extend a foundation that has matured, or else to unpick the alterations of previous generations.

David Chipperfield Architects has worked on museums at every stage in their development, from creating a new building for a new institution even before a director has been appointed, or a collecting policy has been identified, to reinvigorating long established museums. Their commissions can outlast several directors, or turn into a close partnership with just one for the long term.

The West Bund Museum is a case of a museum designed before its content was precisely defined. When it opens in Shanghai in 2019 it will accommodate the first Asian outpost of the Centre Pompidou. It was built by the Chinese government, as part of an enormously ambitious project to turn a stretch of what was once an industrial waterfront on the Huangpu river into a cultural district. And unlike the example of the Guggenheim’s sensationalist architectural approach to its franchises, Chipperfield’s work on the West Bund is rooted in place making and civic values rather than spectacle.

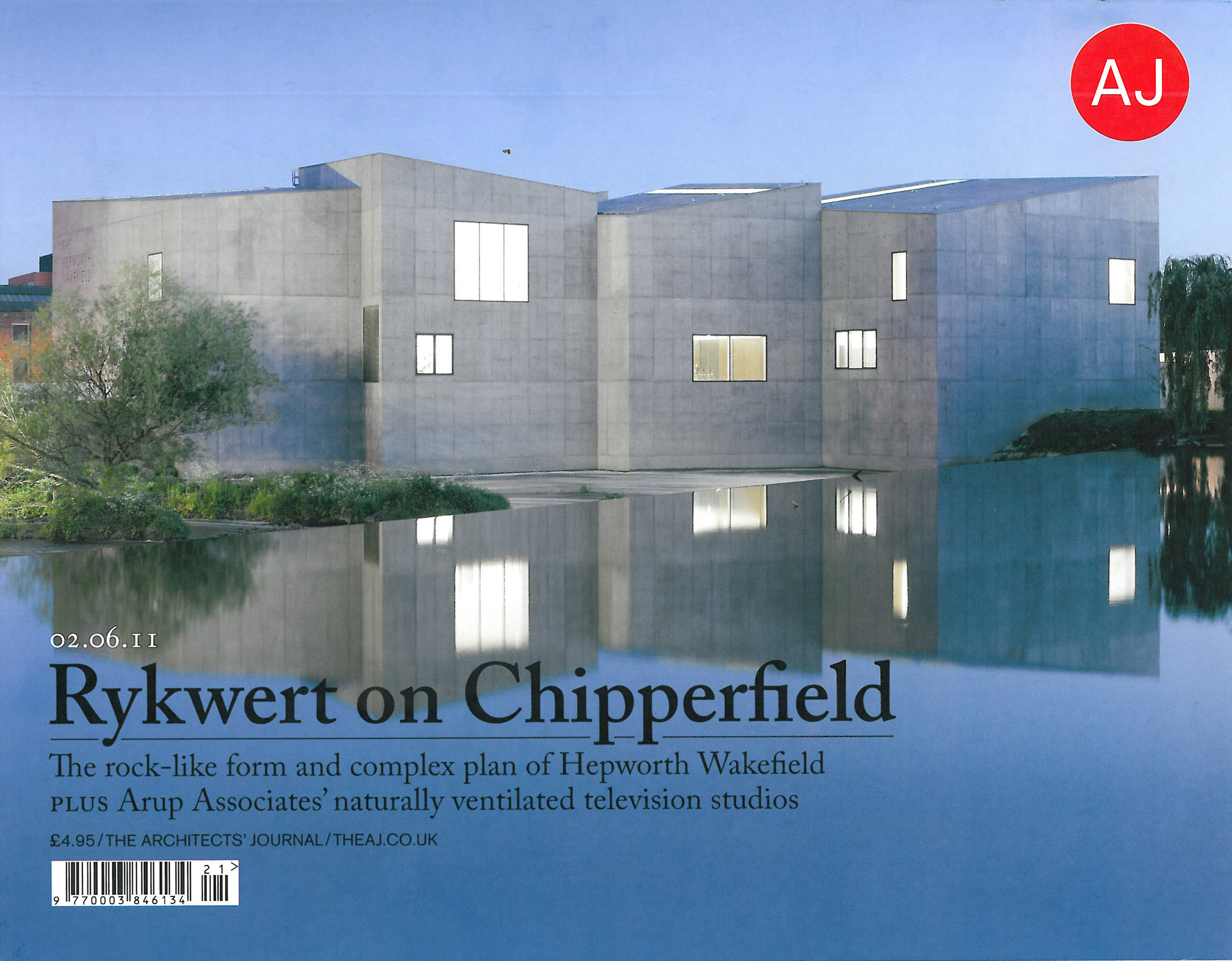

By comparison the Turner Contemporary in Margate is tiny, but in its own context it serves as an equally powerful catalyst for regeneration. It attempts to use a cultural investment to inject new life and energy into a fading seaside town no longer as attractive as it was when William Turner, one of Britain’s greatest painters, spent his summers there. Museo Jumex in Mexico City was built to accommodate a single contemporary collection assembled by a very successful businessman. The Hepworth Wakefield gallery in Yorkshire is named for another distinguished artist with strong local roots. The Kunsthaus Zürich is a civic museum, as in a very different way is the Saint Louis Museum. Zurich is focussed on modern and contemporary art, while Saint Louis is an attempt at a universal museum on the model of the Metropolitan in New York where Chipperfield is now working on a substantial new intervention to accommodate its contemporary art collection.

These are projects that reflect different kinds of museums, as well as very different circumstances. Museo Jumex sits next to one of the most flamboyant new structures in the city, designed by the architect Fernando Romero for the collection of Carlos Slim, in the midst of a new commercial and business centre developed by Slim. In Saint Louis, Chipperfield has made an addition to a classical building. In Zurich, the new building takes the form of independent self contained structure, positioned in dialogue with the original building to create an urban space.

Against Dramatization

A museum that shows natural history, or cars, or decorative must offer a different context for its content from one that is rooted in art. The former are more like theatres than galleries. They are places that involve more extensive scenography which provides a narrative and a framing.

Art on the other hand suffers from curation that is too heavy handed, or architecture that is too insistent, even if it is designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Like a church, the art museum which relies too much on a theatrical interior for its effects risks being seen as insincere, cynical and shallow. Chipperfield has always seen a need for an architect to exercise self discipline, to ensure that architecture should not draw attention away from the contents of a museum.

The most significant quality that Chipperfield’s approach to architecture offers to a museum is a sense of authenticity. His model is more church than theatre, and still less architectural sculpture. The way in which Chipperfield achieves this is through the restrained solidity of his buildings, relying on proportion and spatial planning for effects, and perhaps most of all, the use of natural light. Natural light offers not just a way to look at art, but also to see the architectural substance of a museum. By allowing the outside world in, the building reveals itself, rather than presenting itself as a container filled with theatrical experiences.

Chipperfield has always tried to dissolve the distinction between container and content. And those of his projects where he has lost control of content have always troubled him. However museums are not shaped only by their architects. They have curators and directors, and trustees. And for curators, natural light is far less of a preoccupation than it is for architects. At the opening of both the Turner, and Jumex, the opening displays were all lit by artificial light, with windows carefully blacked out.

The global wave of museum building is accelerating rather than declining. Museums represent rare opportunities to create public or semi public spaces with a sense of generosity that are driven by more than utility, expediency or the single minded pursuit of short term financial returns. For architects they have become a kind of refuge in which to pursue social and spatial concerns where there is much more room to manoeuvre than with the skin of a high rise office tower, the systems management of a hospital or an airport, and more sense of egalitarianism than with the individual house.

The museum has moved far beyond Smirke and Schinkel’s conception of what it might be. In their day, admission was by appointment, and only in the hours of daylight. Chipperfield’s museums have climate control and shops, cafés and learning centres and all the other fashionable essentials of the present day. But it is the sense that he is building on the foundations of his predecessors, and aware of the culture of museums that makes his contribution to this generation of museum building so valuable, and so impressive