The February 2020 issue of Domus magazine, guest-edited by David Chipperfield, highlighted the critical need for social housing provision worldwide based on an understanding of housing as a fundamental human right, and called for the architecture and design community to generate new visions for sustainable places to live.

Entering London from the west, it is impossible to ignore Grenfell Tower, the 27-storey council block that caught fire in 2017 and burned for 60 hours, killing 72 people and causing as many injuries. Now wrapped in white tarpaulin, this haunting monument stands not only as a reminder of poor regulations and maintenance, but also as a symbol of the social inequality and indifference that permeates many of the world’s towns and cities.

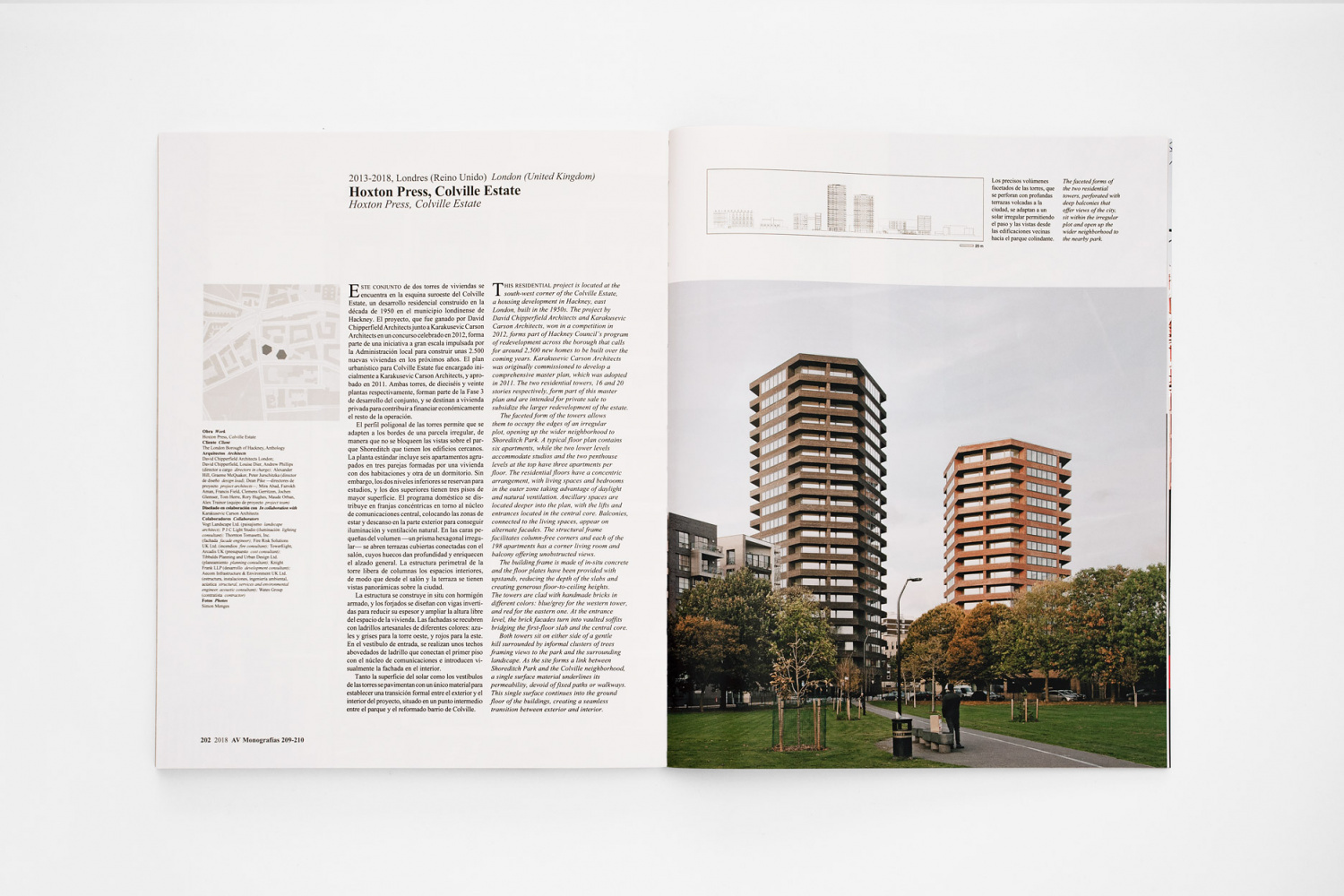

Meanwhile, in other parts of London, new luxury towers spring up as symbols of the exploitation of land value and global investment. The apparent absence of planning strategies is typical of this type of residential investment project in many cities. While individually they might have reasonable architectural ambitions and be well built, they explicitly avoid participating in the building of a healthy city – one that requires a social dimension, as well as individual comfort, security and services. Given that these projects are reasonably protected by their own commercial framework, we might expect them to be more exemplary in their contribution to the identity of the urban environment. Yet they remain absorbed in their own commercial criteria.

But more critical than their lack of urban quality is a tendency towards physical and social isolation. This separation from the surrounding fabric amplifies the idea of the city not as a connective physical territory with subtle thresholds and vibrant overlaps, where people of different backgrounds can freely mix, but as a series of zones defined by economic criteria and commercial performance. This may be comforting to people within the enclosure, but it offers no model for those outside. Perhaps unwittingly, this approach exaggerates divisions and ignores the idea of the city as a shared space, the basis of community.

The character of any settlement is largely defined by the way people live in it. Housing is fundamental to the social structure of any town or city. To truly provide the positive physical environment that should ground our sense of belonging, they must be models of inclusion. They must be planned with intention. And the result should be determined by more than financial motivation or reluctant responsibility. This is because housing is not a commodity; it is crucial to who we are as people. Yet today’s cities are more socially and economically segregated than ever.

Today, good quality and affordable housing is not a market priority. Nor does it seem to be taken as a public responsibility – and certainly not in a form that promotes a sense of community or quality of life. The free market has the capacity to be inventive and resourceful, yet in the case of housing, it remains clumsy and conservative, rarely contributing to qualities that are deemed to sit outside to commercial success. The post-war years saw great innovation in social housing – in fact this was the territory where the most interesting architecture was generated. Admittedly many were poorly conceived and even more poorly realised or maintained, yet others were exemplars that demonstrated ideas beyond the simply expedient. But coordinated proposals that consider housing as a right, as well as a critical part in the building of a better society, have gone largely forgotten.

Housing is one of the biggest challenges of our time. According to the UN, more than 50 per cent of the world’s population lives in cities, and of that number an unacceptably high percentage live in transient or temporary situations. This problem can no longer be defined as an emergency, nor is it limited to “developing” countries. It challenges our conventional ideas of the city while threatening the basic human right to live in dignity. As Paolo Berdini writes (page 11), building enough housing, anywhere, requires continuous negotiation between numerous stakeholders. It also requires sensitive, context-based solutions. Successful housing schemes require a new-found recognition of the fundamental value of place, environment and community. While this cannot compensate for issues of health, security or education, all aspects for which our politicians and leaders must be held responsible, it can at least help build a sense of belonging.

The need to provide housing and build communities of all scales also involves facing up to the environmental challenges in front of us. The irresponsible construction of low-density housing on peripheral and green land is motivated by convenience and transactional enterprise at the expense of natural resources. Meanwhile, in our cities the thoughtless construction of repetitive blocks of housing, with no consideration of community, leads to the slums of tomorrow. Our current solutions are neither appropriate nor sustainable. Left to its own devices, the private sector will not take responsibility for planning, for reducing environmental impact, or for instigating typologies that prioritise social cohesion over financial efficiency. Moreover, we see little evidence universally of the type of political engagement and stimulation required. But we cannot continue to simply imagine that somewhere between luxury investment speculation and emergency shelter we can build homes for people and nurture communities while sustaining the planet’s resources.

Only if we seriously address the issue of housing – and specifically social housing – can we really begin to confront the dual crises of social inequality and the environment. As architects, planners and designers, we already know that the design of our environment and the thoughtful planning of housing are fundamental to our lives. Nor do we need reminding that we have a significant role to play in this process. For too long we have looked on as observers, somehow excluded from the process either because of political isolation or commercial complicity, convinced of our helpless and hopeless detachment. If we don’t take up this challenge, who will?