Rigorous. Rational. Weighty. These words imply seriousness. They also begin to evoke the work of David Chipperfield Architects, one of the world’s leading practices whose work encompasses civic, commercial, cultural projects, private houses, and, increasingly, multifamily urban housing. These multifamily buildings – while not as well-known as their great museums – have a quiet power. And though they are expressions of the advanced capitalist world in which architecture now operates, they also represent a stubborn resistance, a necessary corrective to the disposable housing that markets encourage and often demand.

Rigorous. Rational. Weighty. These words imply seriousness. They also begin to evoke the work of David Chipperfield Architects, one of the world’s leading practices whose work encompasses civic, commercial, cultural projects, private houses, and, increasingly, multifamily urban housing. These multifamily buildings – while not as well-known as their great museums – have a quiet power. And though they are expressions of the advanced capitalist world in which architecture now operates, they also represent a stubborn resistance, a necessary corrective to the disposable housing that markets encourage and often demand.

If you speak to David Chipperfield or hear him lecture, you will sense his seriousness, tinged with world-weariness. You may also get a glimpse of his humour, his wryness. It is somewhere in the juncture between seriousness, worldliness, and intelligent wit, that his deeply humane and dignified architecture is formed (that is not to say that he is the sole author of his buildings – we all know that that is not how a studio such as David Chipperfield Architects operates – but David’s imprint and values informs all the firm’s work). He is also – to use an unfashionable word – a man of taste. Taste, not in the superficial or snobbish sense, but in the sense of discernment, of fitness. He is concerned with the substance of architecture – form, space, light, proportion, materiality – elements he consistently combines in ways that feel just right.

Chipperfield’s embodiment of taste is – I think – why his work resonates, and why his buildings are imbued with timelessness. In New York, I have been watching The Bryant rise along the southern edge of Bryant Park, one of New York City’s great parks, an urban room that forms one of the best public spaces in Manhattan. Operating under the restrictions of local landmarks rules, David Chipperfield Architects has created a building of urbanity and reserve, a building that contributes to the ensemble while subtly reflecting the expectations of today’s upmarket buyers. The facades’ cast stone panels, which incorporate a mix of stone aggregate of the same type as nearby historic buildings, counter the fad for all-glass residential buildings (the cheap curtainwalls are often interchangeable with office buildings). The thickness of the panels and the inset of windows gives the building depth, shadow, and character, in keeping with the masonry buildings around it. Floor to ceiling operable sliding windows with Juliet balconies create a strong indoor/outdoor connection, which is particularly desirable at this leafy, parkside location, and, again, counters the hermetically-sealed standard of many new residential buildings. The building is polite, principled, and urbane.

David has often spoken about how he uses large-scale models during the design process to create a more immediate approximation of his architecture. In 2011 he was the Norman R. Foster Visiting Professor at the Yale School of Architecture, the first person to hold this position. In his studio, his students worked primarily in models at ½” scale, which made a lasting impression on the school. His studio’s iterations of models were piled higher than the bridges crossing the soaring interior of Rudolph Hall. He was an incredible design critic. We also all remember his white trousers.

To call Chipperfield’s work rational is to imply it is cold, or, in the Miesian sense, de-materialized or universalized space. In fact, it is the opposite. It is rational, in that it makes sense. It is intuitive (a word too often applied to technology). In today’s world, where anxieties are exploited for politics and for profit, perhaps most dramatically in global cities, the rational is a kind of balm. In it, we find serenity, and in serenity, a kind of freedom.

Timeless Grids

Perhaps it is Chipperfield’s repeated use of grids, and his classical notion of the base, shaft, and crown that give his buildings their timeless quality. Like at The Bryant, at the Westkaai Towers in Antwerp, a project that was carried out by David Chipperfield Architects Berlin, this language is used, and a few simple moves show how a limited number of elements can be deployed to create meaningful variations and a dialogue between buildings. The two towers are both 15 stories high, but they have different articulations. Tower 3 features projecting balconies, while Tower 4’s elevations are flattened and dominated by the grid, echoing Aldo Rossi. Never the preening soloist, Chipperfield plays to the ensemble.

Timeless yet contemporary, a seeming contradiction. Not so in the hands of Chipperfield. Take for example, his firm’s housing at One Kensington Gardens, where the architects knit together historic brick and masonry facades with taut new buildings with grids that vary in relation to their contexts in this full-block site. Consistent use of materials creates a sense of unity and harmony even as the grids shift and change – sometimes frames, sometimes columns – around the site. Solid bronze balustrades and window frames add luster and contrast. Internal courtyards allow natural light to penetrate the housing block and create visual and social connections among residents. David Chipperfield Architects’ work is legibly new, yet the buildings are informed by their historic context and ancient ideas for how the individual can live well within a metropolis.

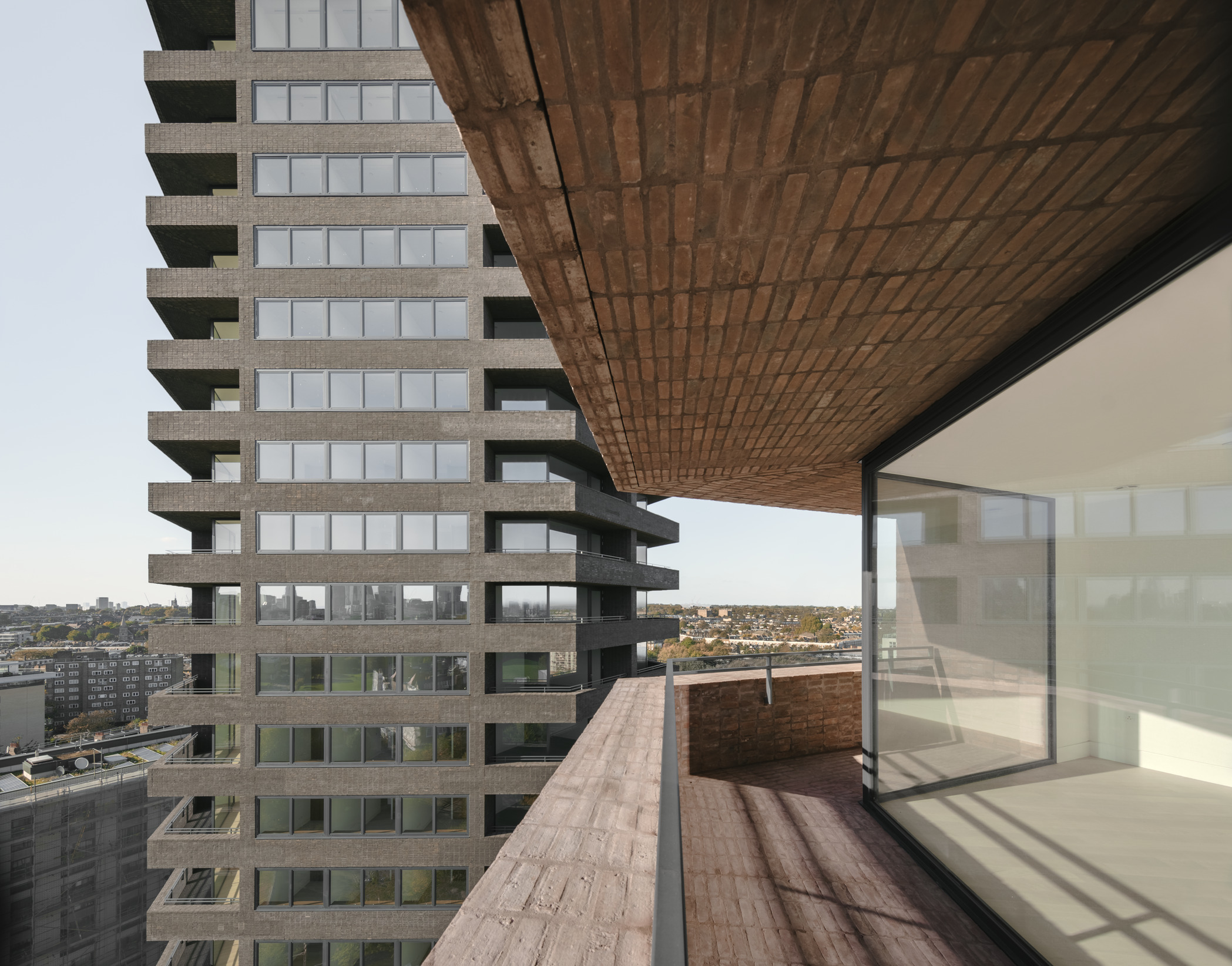

Also in London, David Chipperfield Architects is currently completing two towers called Hoxton Press at the Colville Estate. Part of the Hackney Council’s redevelopment plan, Hoxton Press will help fund new housing in the borough (a total of 2,500 units are called for in the masterplan). Hexagonal in plan, the 16 and 20 story towers take advantage of an irregular site. Each of the 198 units, even the studio apartments, has a generous balcony, with sweeping city views, including vistas of Shoreditch Park. Bedrooms and living rooms are arranged with maximum access to light and air, while service spaces like bathrooms, closets, and kitchens are closer to the core. Even in small flats, this arrangement creates a sense of compression that then leads to expansion, dignifying one’s sense of arrival and procession through the space. Handmade bricks clad the buildings. On the ground floor, the same bricks are used on vaulted ceilings, giving the spaces heft and solidity, a rootedness that is characteristic of Chipperfield’s work.

Working with Herzog & de Meuron’s masterplan, David Chipperfield Architects are designing 11 new buildings in La Confluence, an extension of the city center of Lyon between the Rhone and Soane rivers. In an interview with Le Moniteur, Chipperfield called La Confluence “an opportunity to make a serious piece of city.” Indeed, it promises to be David Chipperfield Architects’ most expansive urban ensemble to date. In an uncharacteristically charitable assessment of his fellow professionals, Chipperfield added: “As architects, we like for our work to have some kind of meaning – not merely to be a self-promotional object.” Certainly our cities – and our lives as citizens – would be richer if more architects thought and designed with some of the gravitas, commitment, and humility of David Chipperfield.