The narrative of contemporary commercial architecture features a number of stories that intersect.

The narrative of contemporary commercial architecture features a number of stories that intersect. For a start, there is the demise of the public sector as developer. We now depend almost exclusively on private investment.

The question is, what gives shape to a city? How should it look? The idea of town planning now seems rather old-fashioned and romantic. In the UK it appears only as a controlling mechanism.

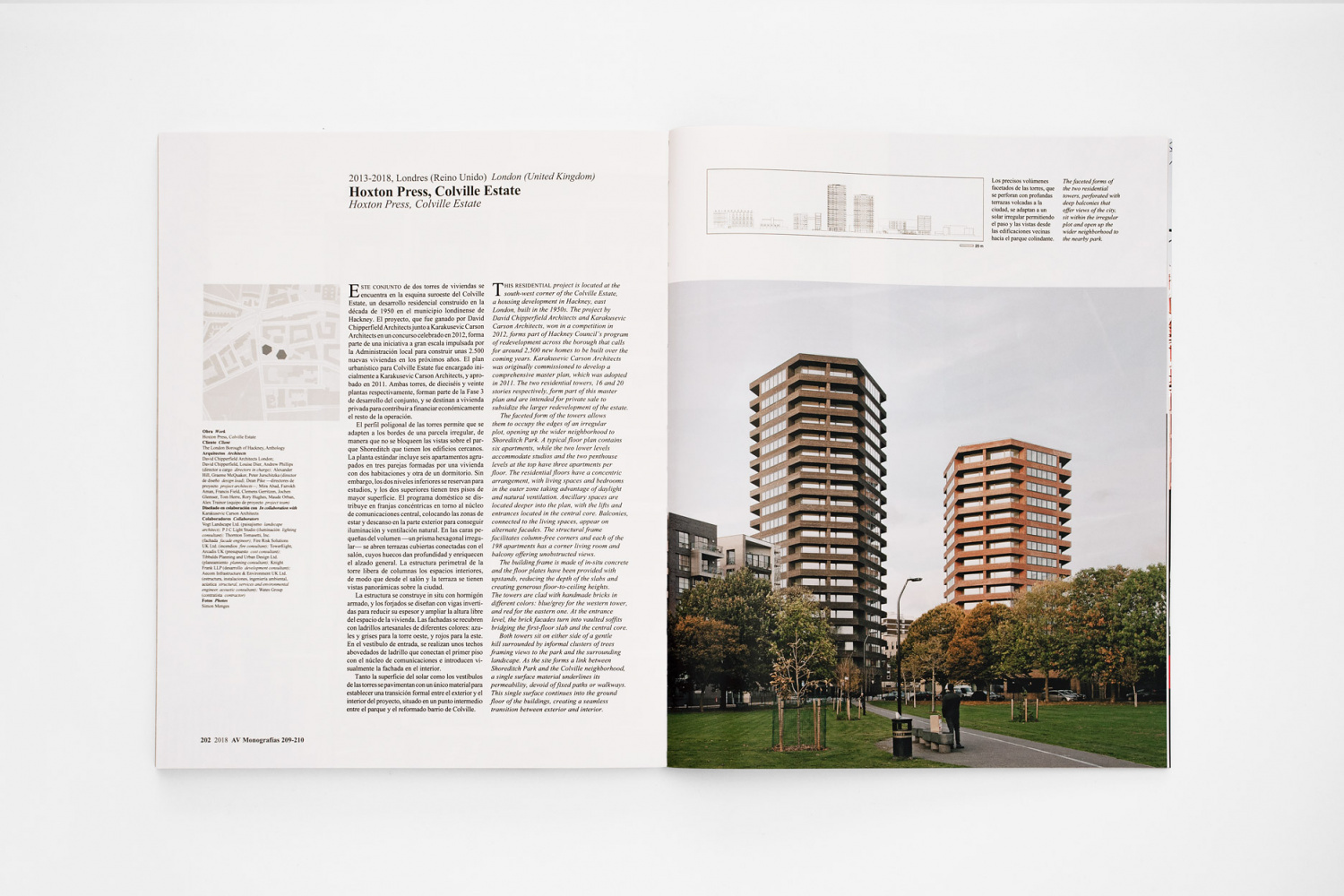

In Germany, for instance, Frank Gehry is to build a tower on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz. There has been a huge public reaction. It is actually a very reasonable tower, but Berlin has been shocked by the idea that the future appearance of the city is being determined not by city planners but by developers.

Berlin does not have the same huge investment momentum as London, so there is more time to discuss what things look like. In London there is huge investment, but the planners are overworked and there is too little time to discuss the implications. On the continent, though, they see it another way and can only dream of the scale of investment in London. Of course, you want investment, but how do you do it? Do you want it restricted or directed? How do you evaluate and assess development? By the amount that gets built or by the quality of what you leave?

There are three issues facing development. The first is aesthetic and, perhaps surprisingly for an architect, that is probably the easiest. The second is the social dimension. In London, as values rise you get a cleansing of building typology and social mix. The centre of the city becomes a wealthy ghetto. The life of the city depends on diversity, but do you accept this cleansing just as part of development or do you say you need to adopt mechanisms to deal with it?

The third issue is scale. If there is one thing we have learnt from the historic city it is that there needs to be a human scale. Our historic cities were shaped by the technical, social and economic limitations of the time. Now that those limitations have been removed we can build anything. So the question is whether we impose limitations on the scale of development – and hinder investment – or veer towards a free-market approach and let these things happen.

As architects, the things we tend to like the most, that affect us the most, are the smaller things. In Berlin I look out of my apartment on to a scene of buildings of four or five storeys, with people in the streets, a small courtyard and a café. But when you move to a different scale the things that link us to the city are removed. Take London’s Shard: it is quite beautiful in many ways, but I can’t relate to it – there is always a distance. Architecture has become something that happens to us. Yet we always want to be a part of it, sitting in a town square or a café – that dimension is very difficult.

In Zurich, proposed projects are put into a scale model of the city and there is a high level of discussion. London seems to have abandoned that idea. Instead, there is an anxiety or loss of confidence that results in polarised positions, with developers and architects on one side and everyone else on the other.

Unless we become better at articulating a shared notion of what our cities should look like we will remain stuck.

We have de-professionalised the planning process in the UK. Investment at the level London has needs better planning machinery. We need city architects or planning officers with power. I am sure Peter Rees, City of London planning officer, would say he has done that and assured a quality of building in the City, but what about the rest of the country?

Planners should be able to speak with authority, have time and be treated with respect. We need, together, to picture what the city should look like.

By David Chipperfield (as told to Edwin Heathcote)

Financial Times March 2013