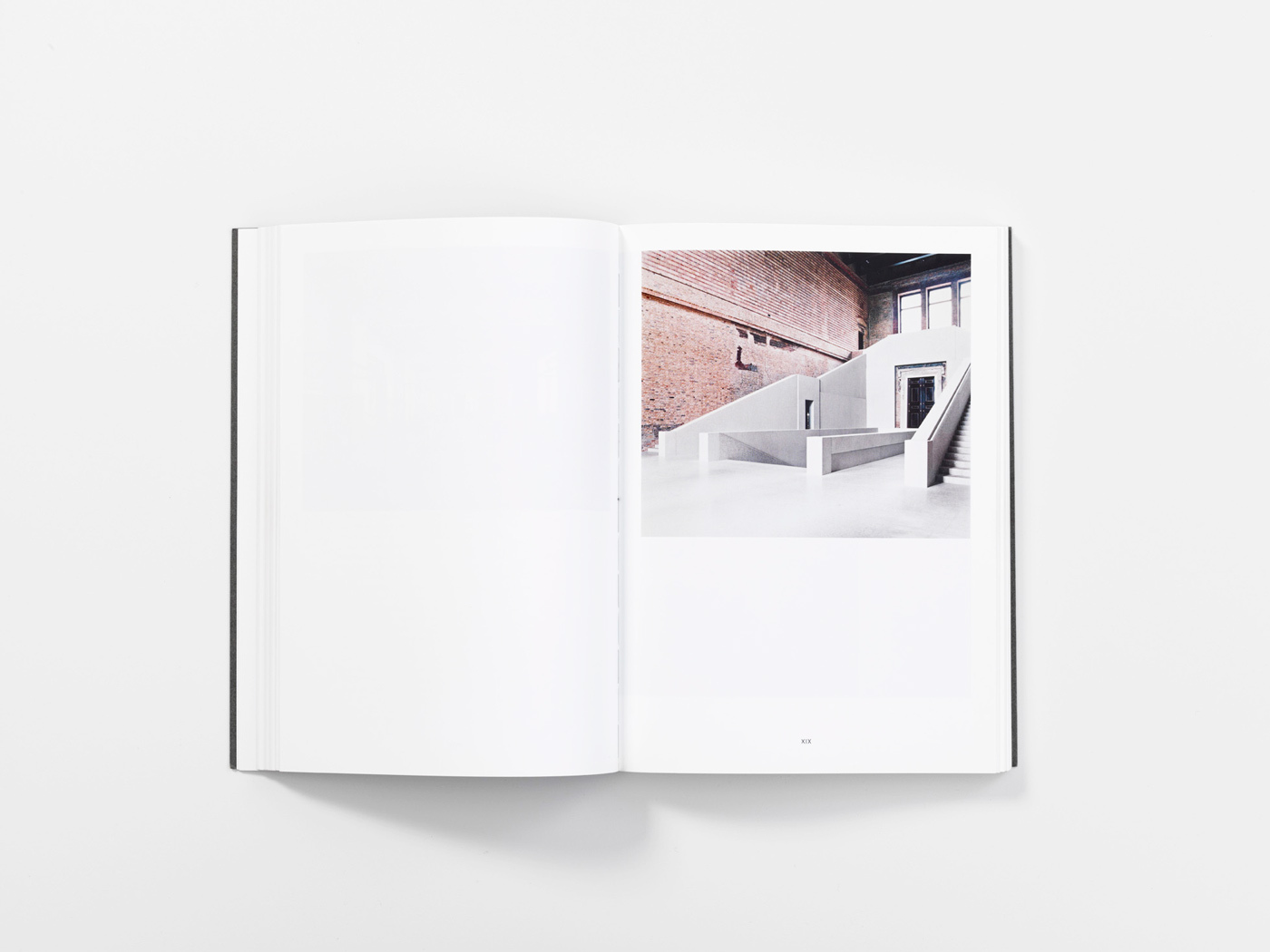

In 2012, David Chipperfield was appointed to direct the 13th International Architecture Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia. Under the theme of ‘Common Ground’, the exhibition included a range of responses which demonstrated the shared ideas and experiences that form the basis of an architectural culture, as well as the wider relationships and resonances between architecture, society, ecology and technology.

These essays have been contributed in response to the theme of the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale, Common Ground. They have accepted the intention of the theme to create a dialogue around the discipline of architecture about what, from our different positions, viewpoints and backgrounds, we share, and how this dialogue might influence our ability to coordinate our resources and our ambitions and give more vision to our collective efforts.

I chose this theme in order to question the priorities that seem to dominate our time, priorities that focus on the individual, on privilege, on the spectacular and the special. These priorities seem to overlook the normal, the social, the common. I was concerned to encourage a more critical examination of what we share, with the awareness of what separates us and how we are all unique. To consider our common influences, concerns and visions may help us better understand the discipline of architecture and its relation to society.

The ambition of the biennale is to emphasise the existence of an architectural culture, made up not just of singular talents, enthusiasms and haphazard moments of creativity but of a diverse complexity of ideas and research united in a common and continuous history, common ambitions, common predicaments and shared ideals. I saw the biennale as an opportunity to encourage my colleagues to address the perception that recent architectural production has been dominated by image, form-making and novelty and to reassert the real research and concerns that lie behind their work and, by inference, that of the larger architectural community.

Within the context of the architecture biennale, Common Ground evokes the image not only of shared space and community but of a rich ground of history, language, image and experience, engaging layers of explicit and subliminal material that form our memories and shape our judgements. The idea of the shared, the common, brings us to consider those things we value and inevitably to the familiar and the known. It is critical that responding only to the familiar and reinforcing our expectations doesn't become an excuse for sentimentality or resistance to progress and research. Sentimentality invariably and understandably justifies the opposing gestures of discontinuity and maintains the prejudiced confrontation between conservative and avant-garde positions. These prejudices must be carefully examined if we are not to regard what has come before as something to escape from and if we are to contribute to a cumulative and evolving architectural culture rather than producing a random flow of meaningless images and forms.

While the biennale theme encourages the exploration of shared ideas and affinities within the profession, the common ground that we must determine is that between the profession and the society it wishes to represent. Architecture requires collaboration, and most importantly it is susceptible to the quality of this collaboration. It is difficult to think of another peaceful activity that draws on so many diverse contributions and expectations. It involves commercial forces and social vision; it must deal with the wishes of institutions and corporations and the needs and desires of individuals. Whether we articulate it or not, every major construction is an amazing testament to our ability to join forces and make something on behalf of others. The fact that this effort is so often regarded as negative rather than impressive, only confirms the dysfunctional nature of this process and the difficulty of coordinating commercial forces and public will. Good architecture doesn't happen naturally, it requires a conspiracy of circumstances and participants. While architects can provide ideas and visions, the relevance of these ideas depends on a meaningful engagement with the society they presume to serve.

While good architecture has always involved an attitude of resistance, to the elements and to the forces of chaos and even resistance to norms and prevailing tastes, this attitude shouldn't become, as it has so often, the justification for isolation and rhetoric. In fact the predicament of the architect is at best one of critical compliance. They are both antagonists and service providers. Architects can only operate through the mechanisms that commission them and which regulate their efforts. Their ideas are dependent on and validated by the reaction of the society it desires to represent. This relationship is not only practical but concerns the very meaning of the architect's work. In the increasingly complex confrontation between the commercial motivations of development and the persistent desire for a considered and comfortable environment, there seems to be little meaningful dialogue. If we intend good architecture to be not for the privileged and exceptional moments of our built world, we must find a more engaged collaboration between the vision of architects and the expectations of society.

While the consideration of the role of architecture involves us in these larger concerns, it is within the discipline of architecture and its distinct physical limits that we must operate. In architecture everything begins with the ground. It is our physical datum, where we make the first mark, digging the foundations that will support our shelter. On the ground we draw the line that defines the boundary of what is enclosed and what is common. While today our relationship to the ground is no longer as profound as in centuries past, it remains critical to our understanding of our place in the world and where we stand.

The physical process of construction and enclosure not only protects but also defines inside from outside, private from public, the individual from the community. As we seem to increasingly indulge the aspirations of the individual, the idea of community, the civic, the public, the common, becomes more difficult to define. While we still long for the things in a city that suggest collective identity-great institutions, a owntown, piazzas and places of public theatre – too often cities can be seen as the disappointing physical result of a discordant relationship between the individual and the collective.

The territory of architecture has been reduced in many cases to maximising size and density on a given site, and achieving some vague sen.se of compatibility with a context. Against this background we try to maintain ideas about the public realm, but they seem to manifest themselves most frequently as choreographed retail opportunities for office workers or leisure shoppers. In this inevitable and never-ending struggle 'to give identity to buildings and spaces, we don't seem to have the mechanisms to help us replace lost visions with new ones.

The theme of Common Ground asks us to think about the physical expression of our collective aspirations and those of society, and to remind us to consider our shared history, to think about the collaborative nature of architecture and the extraordinary potential of its collective process. Today, the symbolic potential of architecture seems to make us uncomfortable but at the same time we acknowledge that the imperative of functionality is no longer an excuse for form. We are subsequently in danger of accepting that our cities, and therefore our lives, are shaped not by purpose but by the commercial pressures of development and decorated by the exceptional moments of our creative ventures.