Any house – even a hut – you build embodies a history, that of its own building. For a public institution, the actual business of building may have a complicated backlog of debates and even quarrels that have shaped it. After it is built, time will alter and modify it, year by year. Every overlay or intrusion will add to or disturb its patination.

Any house – even a hut – you build embodies a history, that of its own building. For a public institution, the actual business of building may have a complicated backlog of debates and even quarrels that have shaped it. After it is built, time will alter and modify it, year by year. Every overlay or intrusion will add to or disturb its patination.

The Neues Museum has passed through more history in its century and a half than most buildings. When August Stüler designed it, he was relatively young, at the outset of a successful career, the favoured pupil and assistant of the great Schinkel. The new building he proposed was to stand adjoining (and at right angles to) his teacher’s masterpiece, which thus became the Old orAltes Museum, whose Ionic colonnade affirmed Berlin’s claim to be the newAthens.And he connected the two with a bridge over the street (now Bodestraße), as if with an umbilical cord.

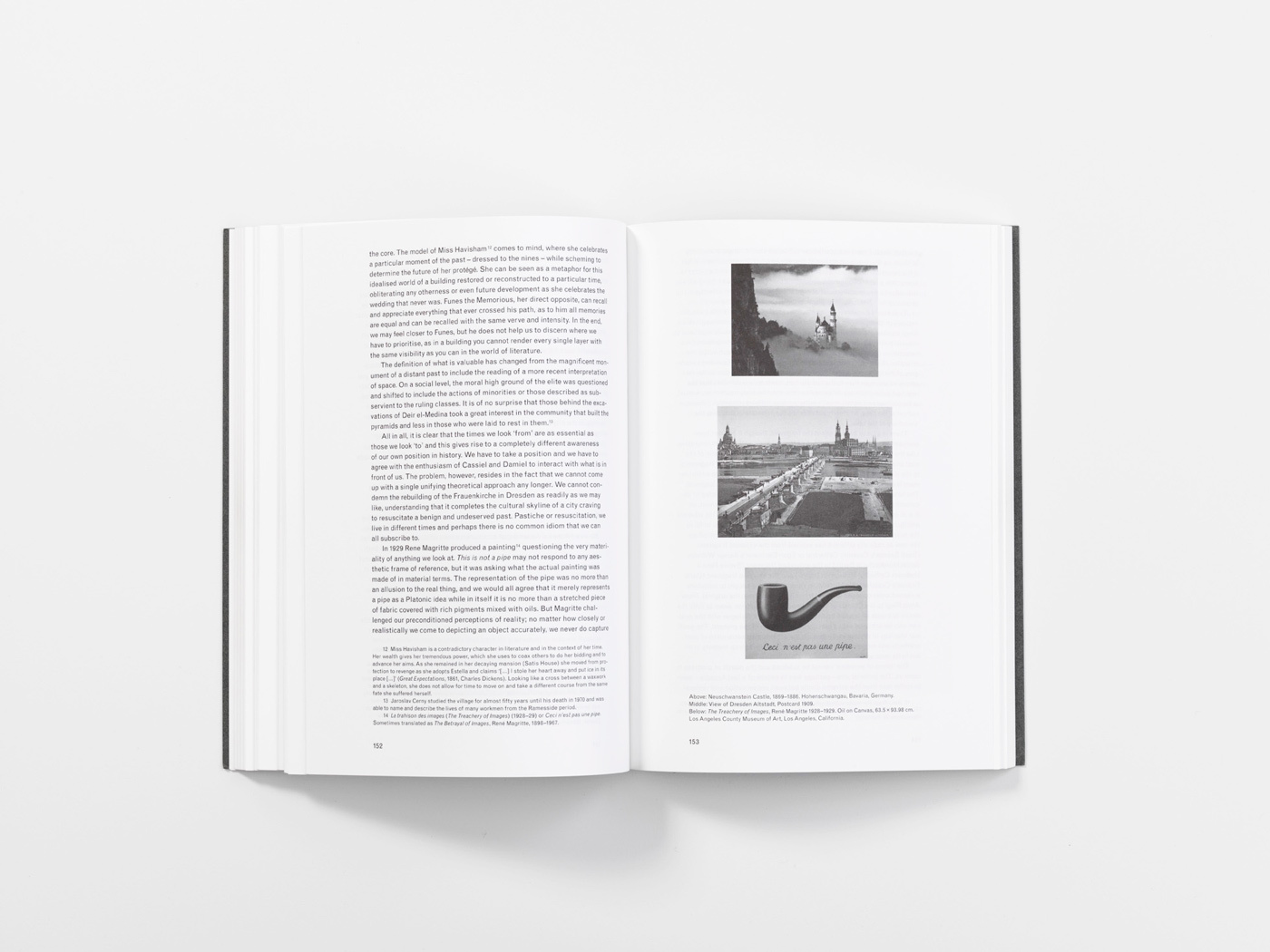

The Neues Museum was to be the first portion of Stüler’s and the Prussian king’s larger plan for what is Museum Island, now designated a World Heritage Site. FrederickWilliam IV, the ‘enthroned romantic’, inherited the Prussian Kingdom in 1840; he had studied architecture with Schinkel, and as a draughtsman he was both fluent and visionary. It was very much part of his plan for the capital that the northern part of the Spree island extending from the Palace and the Lustgarten should become the new spiritual and intellectual centre of his realm, a forum sheltered from the worldly bustle of Unter den Linden. It was to incorporate academies, the new university and a Cathedral (which was built much later, but on the east side of the Lustgarten) with a Campo Santo for the monuments of Prussian royalty and other worthies. The stately colonnade of Schinkel’s Altes Museum would be a frontispiece for this ensemble.

Meanwhile, that Museum had been filled to overflowing. The post-Napoleonic frenzy for accumulating works of art, mostly from the Mediterranean, stimulated a competition for primacy among princes and governments, and Prussia was at its forefront. Where original masterpieces were not to be had, plaster casts would have to make do. By 1841 the need for more space prompted various proposals. Schinkel had died that year and the king inevitably chose his natural successor, Stüler, to trace the outlines of that majestic forum and to design the Museum. Its first instalment was a Doric stoa which was to link its future buildings.

Taking the Doric columns of that stoa as his base, Stüler designed a tripartite structure over it: the ground floor of his building took up the proportions of the colonnades, while the main storey was Ionic, the attic Corinthian. So far it followed the conventional superposition of the orders. But the way the exhibits were organised within that space also suggested another kind of tri-partition – that division into the symbolic, the classical and the romantic periods which formed the evolutionary account of human history expounded in G.W.F. Hegel’s famous lectures on aesthetics that he had given during the 1820s in Berlin but which were not published until after his death in 1835. It is doubtful if Stüler, who was no theorist, was aware of such speculations. Frederick William IV for his part may have detested Hegel, but the grand historical scheme was widely discussed and seductive; it would certainly have been well-known to others involved in conceiving the museum’s direction.

That is why the prehistoric and early history rooms, the ethnographic collection and the Egyptian section with its miniature of the Ramesseum in West Thebes, whose glass roof turned it into a solemn court, were at ground level, as was the Historic Hall in the north-west corner, whose ceiling was supported by proto-Doric columns based on those at the Beni Hasan tombs. The construction details and surface finishes harmonised with the ordering. At this level the roof is vaulted and solid, and the floors are of terrazzo. The Ionic piano nobile, on the other hand, has marble columns based on those of the Erechtheion porch (Stüler had been the draughtsman for Schinkel’s project for a Greek Royal Palace on The Athenian Acropolis), while its floors are mosaic. Some of the long galleries are roofed in a novel manner: segmental cast-iron flat arches dictate the curve of the vault and are braced by straight rought-iron tie-beams that take up the sideways thrust of the vault. Stüler filled the arcs with filigree figures and ornaments in zinc and brass. The top storey had wooden floors and slender cast-iron supports decoratively clad in die-cast zinc; it accommodated the Kupferstichkabinett, the principal collection of prints and drawings, and a Gothically vaulted chamber, the Sternensaal, for the medieval relics from the royal Hohenzollern art cabinet.

The building was also tripartite in plan: the collections were housed in the long wings, each with an internal courtyard, while the dominant centre of the building was the vast monumental staircase, its tallest element, which rose above the gallery roofs into sculptured pediments. The north and south ends of the eastern facade – the one towards the future forum – were completed by two domed corner pavilions whose cornices were supported by five caryatids each.

Work on the building, which had progressed smoothly until 1848, stalled when the Revolution broke out, with which the King sympathised at first, though he took fright when he realised its implications. That same year, the Frankfurt Parliament offered him the Imperial crown, but he rejected it – he would ‘not pick it out of the gutter’. And although he hesitated to restore order in Berlin by calling in the troops, his treasury was depleted by the events and work stopped for a while.

Still, the King was an active participant in the assembly of the museum interiors. The visitor was introduced through the Doric, vaulted galleries into the staircase hall: as you rose to the principal and classically designed main storey, you passed between casts of the monumental (5.6 metre high) Dioscuri, the twin horse tamers from Quirinal Hill in Rome, fancifully attributed to Praxiteles and Pheidias, and ordered by the King. On turning round at the landing, you looked up at the summit of the stairway to a replica of the Caryatid porch from the Athenian Erechtheion, which was originally surrounded by a blind arcade of Corinthian pilasters.

About the time of the Revolution, the King invited the Munich history painter Wilhelm von Kaulbach to provide the visitor ascending the stair with an overwhelming panoramic vision of all human history and achievement: it was to be the climax of the museum. Kaulbach was a disciple of the same Peter von Cornelius who had decorated the Glyptothek in Munich and had, a decade earlier, moved to Berlin to paint the frescoes for the proposed Campo Santo (which was not to be). He was not well received and in the end only executed Schinkel’s panorama of human progress in the portico of the Altes Museum – just completed at the time. Kaulbach’s early fame as the ‘German Hogarth’ had been diverted by his ambition to paint history: ‘We must paint only history! History is the religion of our times! Only history is contemporary!’ he was quoted as commanding. (1)

The whole panorama of human history was therefore summarised in six panels, each 7.5 metres long, separated and framed by decorative adjuncts, mostly in grisaille. The subject of each panel was much discussed. Kaulbach decided to begin with the first historical act, the fall of the Tower of Babel – in accordance with the vision of the history of human freedom held by his Munich friend Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling, who had also moved to Berlin in 1841 and was an opponent of Hegel. The cycle culminated in a complex Reformation scene, a group of many figures surrounding Luther holding up his Bible.

Kaulbach took from 1848 to 1866 to paint the panels, using the laborious novel technique of stereochromy (or mineral painting) directly on the plaster. The panorama became his best-known work, and for a while enjoyed greater fame than the building that housed it. It was much discussed and published, and both emulated and caricatured. The paintings were completely destroyed in the 1943 bombing. Only the cartoons for them survive.

Kaulbach was by far the most famous of the many artists involved in painting the building’s interior. Decorative and stage painters provided each hall with landscapes and historical scenes to create an appropriate setting for the exhibits: Northern mythology, the woodlands of Rügen Island and the shores of the Baltic Sea were the subjects at ground level – along with the much more popular Egyptian themes – while higher up there followed views of Greece, Rome and Italy. Each room was in turn divided into three horizontal zones: the dado and the monochrome walls gave the exhibits a restful background, while the upper sections and the ceiling (notably the ultramarine, elaborately patterned one of the Hall of Mythology suggested by the father of German Egyptology, Richard Lepsius) were given over to the various decorators.

The King’s project for a high, apsed, temple-like building which was to dominate the proposed forum was revived towards the end of his life. Stüler was engaged to develop and interpret the royal sketches, but by then he was withdrawing from directing the Neues Museum works, which he handed over after 1854 to his fellow Schinkel pupil and assistant, FriedrichAdler. Stüler had other important commissions, such as the National Museum in Stockholm. Dying childless in 1861, the King was succeeded by his brother William I, who would be proclaimed Emperor ten years later. The project was now taken over by Johann Heinrich Strack, yet another Schinkel pupil, and he developed it in a much more ornate and sumptuous – incipiently Wilhelminian – manner.When the connoisseur and collector Gustav Waagen died in 1868, leaving his collection to the nation on condition it was given an appropriate building, the destiny of the royal project was sealed and it became the National Gallery (today the Old National Gallery).

The rapid growth of the Berlin collections required further expansion. Much of the Oriental and newly acquired European art was given its own building, the Kaiser Friedrich (now Bode, after its first director) Museum on the northern tip of the island. Between it and the Neues Museum Alfred Messel built the rigidly classicist Pergamon Museum (which is dominated by its vast exhibits as the Neues Museum never was and is to be restored according to designs by Oswald Mathias Ungers) to house the vast finds from that city, as well as the Ishtar gate from Babylon, so completing the Museum Island that is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

When the Neues Museum was adapted for the rather different museography of the 1920s, most of the plaster casts were moved out and the decorative operatic frescoes on the walls panelled over, while the ceilings with their elaborate figure paintings were concealed by plain suspended ones. Paradoxically, these surface coverings were peeled off during the shoring up work of the late 1980s, and the highly decorative interiors have reappeared from underneath them; they bear not only the scars of war damage, but also others inflicted by the anchors from which the lower ceilings had been hung. Bombs and piecemeal repairs thus put paid to the sachlich resurfacing and revealed the more colourful ornament of the original interiors. From the Revolution of 1848 to the destruction of 1943/45, accidents of history have buffeted the Neues Museum, while the philosophers’ vision that moulded its original conception and dictated its ordering no longer speaks to many of us, shattered as it was by the very same events. History as a grand narrative, as it originally shaped the Neues Museum or informed Kaulbach’s vast paintings, no longer corresponds to the way we order our past – which is much more fragmentary, much more concerned with the particular, with micro-histories, with strife and conflict, rather than an epic account of the progression from one epoch to another. That may be why a renewal of the sixfold panorama could not be realistically considered. Even if some way could be found to replace the paintings with replicas of the surviving cartoons, those flaccid and balletic groups of figures would no longer dance for us. Our eyes could not take them in as late-nineteenth-century eyes once did.

This involves a larger issue – that of the protection versus the restoration of historical buildings, a question that has been much debated and even legislated since the mid-nineteenth century. To restore an imperfect building to a supposed once perfect state implies the restorers’ superiority to its fallible builders, while an attempt to return it to its ‘original’ condition suggests that the building has not had a history – or that whatever history it had can be ‘cut off’ at some arbitrary point in time, that there is some state (which must always be a hypothetical one) to which the building can revert.

In the case of the Neues Museum, a decision would therefore have to be taken as to whether it was to be restored to its condition in 1930 (with its neutral museography) or to its 1866 state, when Kaulbach had finished the stereochrome frescoes and the scaffolding was finally removed from the stairway; or even to the project as Stüler first conceived it, with his blind Corinthian pilaster arcades taking the place of the vanished panoramas – which would, of course, have emphasised the vertiginous height of the hall.

Put this way, any such alternatives may seem unacceptable. Even simply repairing the exterior is not a straightforward proposition, as during the wartime catastrophe large areas of stucco fell off the walls. Should what remains be stripped and the whole building be uniformly replastered – or should it be merely patched up? Should the breaks between the surviving old and new stucco be smoothed over or should they be emphasised? And what of the cracked caryatids on the domed corner pavilions of the eastern façade? And the putti built into the stone window frames? There is no way, in any case, to adapt any such approach consistently to both the interior and exterior of this building.

Chipperfield has taken on the challenge frontally: he has chosen to accept all the marks and scars of the building, all the layerings that have taken it from Schinkelian sobriety through Wilhelminian opulence and Weimar Sachlichkeit to end in the raging horrors of the SecondWorldWar, so that the renewed building can stand as a witness to all of its past, shelling and bombing scars, bullet holes and all. Whatever has survived has been retained. The sculptures do not hide their wounds. Those walls that were stripped bare have been tinted and shaded using slurries and glazes, and where the bricks needed completion, local historical ones have been reused. The mosaic and the terrazzo floors have been patched up and smoothed to be serviceable again. The fragments have been gathered so that nothing that survives is lost. The staircase hall in particular had to take on a new role, since Kaulbach’s panoramas and the Erechtheion Caryatids were irrecoverable. The filigree stairway that allowed the walls to dominate the ascent has been transformed into a solid base; above it the sheer surface of the walls is articulated by fine, barely perceptible horizontal rustication that moderates the severe, craggy space. The massive but carefully calibrated detail of steps, balustrade and handrail worked out in finely finished concrete makes the new stairway the proud focus of the whole building. Its breathtaking new vesture offers an eloquent tribute to Stüler’s grandiose but spare proportions.

The reborn building now speaks anew to the visitor in accents that echo the intentions of its original designers and assumes the role of a witness to its own tragic story. Some have found this uncomfortable, while others have called for a ‘total’ restoration, which would only have been possible by glossing over the past. Yet others may prefer a museum neutered to a sterile museality.

For all that, the enthusiasm with which Berliners have crowded into the Neues Museum seems to show that its fresh guise may turn out to offer a testimony that will continue to be a more important Mahnmal than any specific or ‘dedicated’ monument. The fragmented history that it recounts through intricate overlays can speak to our time – and will, I suspect, speak to the future more clearly and sympathetically than did the grand pictorial narratives that it so convincingly presented to the visitors of an earlier age.

To have kept faith with Stüler’s grand and spare proportions, to the inherent structure, has allowed Chipperfield to pay tribute to the harsh contradictions of the Museum’s history while reasserting its unity. That seems to me a great achievement.

1 ‘Geschichte sollen wir malen! Geschichte ist die Religion unserer Zeit! Geschichte allein ist zeitgemäß!’ In Cornelius Gurlitt, Die Deutsche Kunst seit 1800 (4th ed.), Berlin 1924, p. 215.

By Joseph Rykwert

Neues Museum (2009)