Only in Germany do citizens’ action groups and even professionals in the field insist so vehemently that new buildings be designed in a contemporary architectural idiom. It would, however, be a mistake to infer from this that there are more surviving old buildings, against which contemporary architecture would have a hard time asserting itself. The reverse is the case, of course. Germany lost far more of its historical architecture than its European neighbours during World War II, and even more so during the subsequent period of reconstruction, which was nearly always understood and used as an opportunity to build entirely new structures.

Only in Germany do citizens’ action groups and even professionals in the field insist so vehemently that new buildings be designed in a contemporary architectural idiom. It would, however, be a mistake to infer from this that there are more surviving old buildings, against which contemporary architecture would have a hard time asserting itself. The reverse is the case, of course. Germany lost far more of its historical architecture than its European neighbours during World War II, and even more so during the subsequent period of reconstruction, which was nearly always understood and used as an opportunity to build entirely new structures. Nevertheless, the ideology of modernism – overstated in the demand that every period should and must express itself exclusively in its own formal idiom – has retained its validity here. The debates over the restoration or even complete reconstruction of historical buildings have always triggered an irreconcilable conflict between modernists and traditionalists – to put it simply – no matter whether they concern a rapidly changing metropolis like Berlin or a comparatively serene community such as Hildesheim or Halle.

In this difficult country, where debates are always more ideological than pragmatic in nature, David Chipperfield has enjoyed undisputed appreciation. Today, after a remarkable series of wide-ranging projects, he is praised by all sides as an important representative of his field. He is considered neither a modernist nor a traditionalist, and certainly not narrow-minded, but rather a defender of architecture for its own sake, someone guided by common sense more than dogma – an attitude we Germans admire in the English, but for which, revealingly, there is no equivalent phrase in our language. It is generally agreed that the Neues Museum on Berlin’s Museum Island – which is refurbishment, reconstruction and new design in equal measure – is a masterpiece that constitutes a model and scarcely attainable standard for any architectural brief that is even remotely comparable to it. The approval for the building ultimately realised was unprecedented, not despite but precisely because of the fact that the planning for how to deal with the wartime ruin of the Neues Museum was so controversial and, at times, an intense feud. The result persuaded everyone, even the project’s harshest critics.

An architect may not necessarily be comfortable receiving praise for a building that was originally the work of another and, despite complementary restoration, will remain so. Chipperfield in particular is not interested in virtuoso landmark preservation, even when the result, as in the case of the Neues Museum, appears to be just that. Rather, he seeks the connection to history or, more accurately, the continuity of historicity, understanding the past as a tradition that also continues into the present. He is concerned with finding expression for the awareness that architecture is never entirely new, but is based on continuity and hence on fundamental principles. That applies above all to tectonics as an ‘art of assembling’, as defined by Gottfried Semper. And indeed Chipperfield frequently displays the interaction of load and support, of pillar and beam, of vertical and horizontal. Moreover, all architecture is inserted into a context shaped by earlier events. This is not necessarily limited to the immediate architectural context – it can just as easily be the intellectual framework into which the new work has to assert itself.

One outstanding example of this is the Museum of Modern Literature in the Swabian town of Marbach. This town has great symbolic power as the birthplace of Friedrich Schiller and the home of the German Literature Archive. It has changed considerably since German literature went from being an object of admiration to one of critical examination, since ‘national literature’ was replaced by modernism and the literature of exile, condemned by the Nazi regime. Providing these movements of the twentieth century with their own institution was the brief when designing the Museum of Modern Literature on its exposed sloping site. The new building expanded the National Schiller Museum’s forecourt, creating a plaza with the Literature Archive. If that were not traditionalist enough, Chipperfield gave his design echoes of an ancient temple, of a building on a pedestal with a roof resting on supports, above another section set back from the supports. These supports, however, are not columns but square pillars; the roof is flat, without a cornice or a gable, and the pedestal is not the same on all sides but compensates for the slope, into which a lower storey has been inserted on the valley side. Seen from here, the building appears to be a two-storey structure that plays down the initial temple association formed when approached from the other side. The building – which is neither symmetrical along an axis nor in the arrangement of the rooms inside – produces a strange tension with its intended function. That is because modern German literature – which was initially not understood, condemned even, only to achieve recognition later – has a relationship with the land of its language that is anything but unscathed. The break-up of the nation, both in a cultural and a political sense – a fundamental theme of the nineteenth century in Germany – returned in the twentieth, albeit in a highly negative way. Dedicating a building that takes up traditional forms and reformulates them in its own way to this particular literary era is necessarily a perplexing undertaking.

At the same time, Chipperfield achieves something quite astonishing with this building. He manages to reconcile – and to express it with pathos – Germany with the tradition, or rather with the continuity, of architecture. The building invites the re-examination and reconsideration of traditions that had played a large role in the birth of modern German architecture – one need only think of Alfred Messel, Peter Behrens and the connection to architecture ‘around 1800’. Indeed, such an understanding of tradition in general was compromised by the Nazi period, as embodied in the work of Paul Troost and Albert Speer. After World War II, everything traditional, and certainly everything monumental, was considered contaminated. Only an exile like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe could be forgiven for designing his Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in the late 1960s like a temple and even establishing a connection to Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who had been almost entirely forgotten again in Mies’ day.

This does not mean that Chipperfield has only explored this kind of architectural idiom in Germany. The design for Marbach has a precursor in an unrealised proposal from 1999 for the Royal Collections Museum in Madrid. There too the museum was intended to be open facing a sloping terrain on the side, and there too it was to be accessed from above, enabling visitors to see the layout of the rooms as they descended. Similarly, the roof was to be supported by regularly arranged square pillars. But it makes a difference whether a building with such a design is built in Madrid or in Marbach. A design for Marbach cannot be considered independently of Germany’s architectural history, nor certainly of the history of its subject matter. That a manuscript unpublished during its author’s lifetime, and which he wished to be condemned to oblivion, like that of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, should be housed in such a place is not only the triumph of modernism over its detractors but also an act of reconciliation between the Germans and their own fraught history.

This may suggest more meaning and interpretation than the architect would ever claim himself. After all, the slender supports on which the roof in Marbach rests, for example, turn out to be a recurring element in his oeuvre, albeit used in very different ways. When the Museum Folkwang in Essen was being built – much larger than the old building – there were steel supports that articulated the façades of the building and especially the slightly protruding entrance pavilion. The addition’s programme is dedicated to modernist art, which had particularly suffered in Essen under the Nazi regime, but while the building’s restoration by means of calculated acquisitions and reacquisitions represented an outstanding achievement of the post-war era, the viewer is not overwhelmed by any overarching architectural statement. Looking at the sheer functionality of the new rooms and the restrained exterior view of the building, not even its intended purpose as a museum jumps out. What does strike the visitor is the quality of the architecture, which is entirely subordinate to the art shown in it. An addition from 1960 had to make way for Chipperfield’s building, a principle about which he has commented: ‘There is nothing worse than tearing down a building only to replace it with something that isn’t better.’ The decision to demolish the 1960s building was, in his view, ‘a brave one’.

Removing the idea of meaning in the sense of architecture parlante from the specifically German context, one could point to the project currently in development for a museum in Naga in the Sudanese desert. This rectangular hall, which is made rhythmic by a terraced roof, scarcely represents more than the archetypal form of a museum, merely a way of holding objects to protect them from the weather. The construction of massive pillars and beams lends the Naga Museum an archaic look appropriate to the excavation site of an ancient culture in a timeless, inhospitable place. The fact that the buildings from this site, such as the very unusual temple of Hathor from the Hellenistic period, had been reconstructed by the Berlin excavation team – that is, by means of classical anastylosis, which even the dogmatic Venice Charter allows – makes this design even more expressive. At the same time, it reveals a characteristic aspect of an attitude toward design that has often been called ‘minimalist’: returning to basic elements of architecture. The results preserve the continuity of architectural history in a new form without imitating it or, as in post-modernism, ironically quoting it.

Neither imitation nor irony characterises the concept for the Neues Museum either. Chipperfield himself uses the term ‘soft restoration’ to describe an approach that changes from room to room, even from detail to detail. Whereas the other museum buildings on the Museum Island – which were, it should be said, damaged far less and had already been restored to operation – were either reconstructed faithfully with respect to the original (e.g. the Alte Nationalgalerie) or an almost seamless blend of historical elements with contemporary additions (e.g. the Bode Museum), every visitor to the Neues Museum will recognise what is old and what is new, what is damaged, repaired, restored and replaced.

And yet the result is not dissonance but, on the contrary, a harmony of emotional – once one might have said spiritual – power. It is not the fact that the war damage remains visible that is crucial; indeed, the overused concept of simply ‘leaving the wound exposed’ is not embraced by the team. Certainly, the transitions from surviving and restored areas are recognisable, for example in the case of the wall frescoes, which were by and large destroyed. But this is done more in the spirit of John Ruskin’s theory of the monument, which emphasises the ‘picturesque’ aspect of decay. Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who as Prussia’s head architect was responsible for historical preservation, was concerned more about the architectural heritage of the Middle Ages and therefore tended to focus on reinforcing the structure. Chipperfield is perhaps more like Ruskin than Schinkel in this respect, although this does not mean that he does not feel a connection to Schinkel’s buildings.

It is precisely the juxtaposition of the preserved, restored and replaced – confusing as it may be at first glance – and the ‘picturesque’ that makes the Neues Museum so eloquent. The building speaks a double truth: the truth about destruction but also about the architecture of Friedrich August Stüler, which cannot be restored to its original state of around 1850 but can no longer decay into a mere ruin, as was the case for half a century after 1945. The Neues Museum as designed by Chipperfield and his team tells its story, and hence that of Germany, across a century and a half; it tells of an ambition to teach that was the reason it was established, of the progress of scholarship on antiquity, of terrible destruction, of neglect and loss, and finally of a rapprochement with this very history, which can only be taken as a whole. It also tells of the renewal of architectural forms that has taken place during this period and presents its new construction, the north-west wing, self-confidently and without false modesty.

A building designed at the same time as the Neues Museum but completed years before greets it across a side arm of the Spree, and thus seems like a kind of prologue to the Neues Museum. The gallery building ‘Am Kupfergraben 10’ is constructed of the same bricks as the Neues Museum, only here they are not exposed but rather washed with a light slurry. The lintels are concrete beams emphasising the tectonic principle of loading and bearing. This building is, of course, a completely contemporary structure. It stands out powerfully against both the Wilhelmine-era building on the one side and what appears to be a late Baroque building on the other. The irregularly arranged windows of different sizes make their function evident: directing light of varying intensity to specific exhibition spaces. If Chipperfield intended this building to demonstrate that in addition to the restoration work on the museum he could be very modern, and also wanted to say that the choice of materials says nothing about the modernity of a building (as Schinkel had proved before him using simple brick), then the gallery building ‘Am Kupfergraben 10’ is powerful evidence of this.

In the case of the Neues Museum, however, another level of meaning comes to the fore. It could be called an act of reconciliation, had the word itself in connection with the German past not been so discredited. The tribute paid to this building by the large visitor numbers and the naturalness with which it is perceived in its heterogeneous manifestations between preservation and new construction underscore this interpretation. The past never goes away, it cannot be denied, but it leads into the present, which claims and is granted its own place. Moreover, the state of the building corresponds to that of the objects displayed within it. These witnesses of past cultures also bear traces of their historicity, with cracks, fractures and missing pieces. They are precious not only as products of earlier eras but as documents of transience and preservation, as objects of our historical awareness. Rarely does architecture reveal itself as an intellectual achievement as it does in the design of the Neues Museum. ‘For me, an architect has to have an attitude towards life, not buildings,’ says Chipperfield. ‘If something has meaning, it speaks to us, to both our expectations and our memories.’

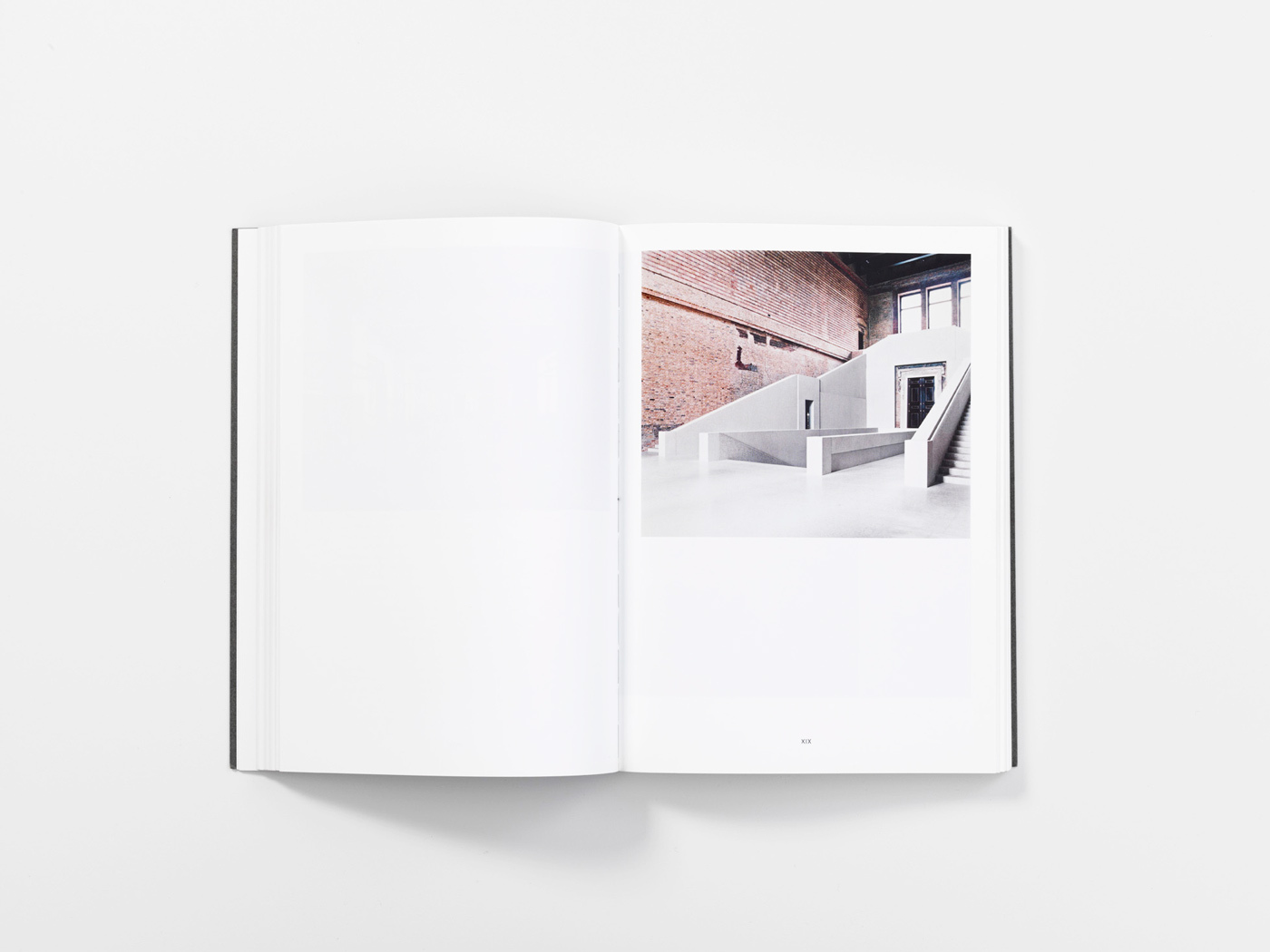

This sort of permeation of ideas is always tied to the specific architectural brief for Chipperfield. The opposite of a dogmatist, the opposite of a signature architect, he reproduces an immediately identifiable type for everyone and every client. His oeuvre is characterised by great diversity, in the dimensions, the forms, the materials and even the palette, though he seldom employs colours. The buildings are, however, characterised by a concentration on the essential aspect of the given task, the given plan for the space. The Miesian ‘less is more’ is also a guideline for him, but not dogmatically so in the sense of a formal asceticism driven to the extreme. Consider the large staircase in the Neues Museum, which was constructed of concrete elements as a deliberate contrast to the destroyed original behind it – albeit very carefully produced concrete: on the one hand, it is an example of optical reduction; on the other, it surprises with lavish details such as the wonderfully shaped handrails. It illustrates for his own outlook something that Chipperfield said about Schinkel and Mies: ‘The connection between these two is a particular type of classicism, one of great refinement.’

By ‘Schinkel and Mies’ he is of course referring to the two museum buildings that bridge nearly a century and a half: the Altes Museum and the Neue Nationalgalerie. No one building on Museum Island can ignore Schinkel’s museum. Chipperfield too alludes to Schinkel’s Altes Museum: ‘The extraordinary thing about the balcony is that Schinkel managed to bring the public garden [Lustgarten] into the museum,’ he once explained. ‘There is a wonderful drawing by his studio of a man and a youth on the balcony. They are in the museum, without having opened a single door. We made use of this invention by Schinkel for the James Simon Gallery.’ The future entrance building to the Museum Island – named after James Simon, the greatest and most selfless patron Berlin has ever known – adopts for its slender supports the motif of the colonnade that Stüler once constructed to visually connect Schinkel’s museum and his own building. With its terrace leading up an open stairway and directly into the museum, and with the columned hall on a tall pedestal facing the water, Chipperfield has translated for our time this Schinkelian idea of dovetailing interior and exterior. Admittedly, Schinkel’s longing for Italy that resonates in this idea may not always be supported by Berlin’s weather.

Reduction means dispensing with the superfluous. Many have pointed to Chipperfield’s early works in Japan: Gotoh Museum, near Tokyo, and the Toyota Auto Building in Kyoto, both of which feature exposed concrete that causes the volume to stand out unmitigated.

In one of his most recent projects – an ensemble of buildings for his own practice in a section of old Berlin characterised by small lots and commercial buildings from the imperial era – this asceticism of materials and formal idiom returns. It must be said, however, that the individual, staggered buildings conceal very distinct solutions for the floor plan. For his first building in Berlin, a private house in the affluent bourgeois neighbourhood of Dahlem, Chipperfield had interlocking spaces of different dimensions, especially in height. For a moment, it is reminiscent of Adolf Loos’ ‘Raumplan’, but without the opulence of expensive materials.

If anything, for Chipperfield the reverse is true: the practice is able to employ ordinary materials in a way that they not only seem precious but actually become so. They are elevated, in the sense of being appropriate. In that respect he resembles Schinkel, who exalted profane brick – the dominant construction material in humble Prussia – and made it his preferred material. For the Neues Museum, bricks from demolished buildings were used, not out of frugality but in order to harmonise the restorations – in the Egyptian Courtyard or the new South Dome Room, for example – with the existing architecture and also out of concern for craftsmanship.

This quality provides one key to understanding his architecture, and the Neues Museum can once again serve as evidence. The South Dome Room, the remains of which were removed during the East German era – had to be recreated. It was built of bricks, not as an identical pendant to the North Dome Room, which survived, albeit with its painted decorations heavily damaged, but with its geometry intact. Out of the square substructure rises, without transition, a cupola with a glass-covered oculus. The imperceptible transition from square to circle in the exposed masonry could not have been calculated by a computer; it depended on the experience and skill of the masons. The result – as spectacular as it is, and as much as it is appreciated by visitors – is almost a homage to the act of building.

Careful craftsmanship, to put it mildly, is neither required nor practised in all countries. It was not least the international modernism of the inter-war period that made it part of its programme that new buildings should have a limited useful life – which suited profit-minded commercial investors and real estate entrepreneurs very well. Thirty years, roughly the duration of a generation, seemed adequate for a building’s lifespan, after which it could make room for new demands and uses. David Chipperfield did not have an easy time in his native country with his ambition for quality. It seems that other countries with better developed craft traditions, such as Germany and Japan, were more understanding. Naturally, Switzerland should be mentioned as well, where his practice is currently involved in planning the extension to the Kunsthaus Zurich. The Swiss sense of quality and what Chipperfield calls ‘refinement’ is well developed, and not just since the minimalists of the Basel School distinguished themselves in this respect.

With an eye to his Swiss colleagues, Chipperfield’s feeling for vernacular architecture should be mentioned. (At the same time, ‘vernacular’ is difficult to translate into German, especially as the word volkstümlich has an unpleasant ring, not least due to the word’s usage by the Nazis.) What can ‘vernacular’ still mean today, after a century of modernism, a century of urbanisation, a century of concrete being available everywhere? It can only be a memory, according to Chipperfield, who based his early River & Rowing Museum in Henle-on-Thames, begun in 1989, on the silhouette of the boathouses and barns there – understandably, as the museum’s collection included the long hulls kept in the boathouses. And yet we see more than a nod to local forms and common materials in the wood panelling of the building. The fact that the museum building had to be placed on a ground sill elevated on concrete supports to protect it from flood waters, and is reached by stairs, made it the kind of museum temple that Schinkel so emphatically illustrated with his design of the Altes Museum.

Chipperfield has all sorts of materials at his disposal: concrete, metal, glass, brick and wood. Nothing is prejudged ‘high’ or ‘low’. His extension to the cemetery on the island of San Michele in Venice is an example. The new tomb walls are executed in concrete – exposed, of course, and very much in contrast to the marble cladding that has been common in Italy since time immemorial. Perhaps concrete – because of its all but unlimited plasticity – is the architect’s favourite material. Especially since concrete can be formed and joined like ancient stone slabs, as in the Neues Museum. The antithesis of such tectonics – and Chipperfield unites a number of apparent antitheses in his work – can be seen in Wakefield in West Yorkshire, northern England. The Hepworth Wakefield, which is dedicated to the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, who was born there, is composed of a group of irregularly formed, angular building blocks that have been forced together into a highly serrated whole, with roofs of different heights that slope in different directions. The building sits on a promontory in the middle of the River Calder, which on one side plunges over a weir to dramatic effect. It is a highly sculptural building, suited to the artist it honours, who is considered one of the protagonists of modernism in the conservative Britain of the inter-war period. Anyone looking at the buildings in this city, hit hard by the de-industrialisation of the north, can imagine what it means to create such a masterpiece of design and execution. Much the same could be said of Margate in the south of England, where a gallery, Turner Contemporary, marks a turning point in the prolonged death throes of a once loved seaside resort.

Why museums and galleries again and again? Chipperfield is not a museum architect but rather the architect of several museums, which represent a relatively small part of his work. Museums have, however, become a sought-after commission today, because, having long since been liberated of their traditional formal idiom of the classical and sublime, they offer great latitude to the architect’s creative imagination. At the same time, museums are points of crystallisation for society, buildings in which the self-image of a place can be expressed. Discussions about such building projects proceed accordingly – at least in Germany, where the economic agendas for building a museum play a more limited role compared to elsewhere.

Architecture is an intellectual activity, and design has to be preceded by thinking. ‘What I find really great about Germany is the way debates are held here. I know of no other country in which people debate and argue with such intensity and on such a high intellectual level,’ said Chipperfield, looking back over more than twelve years working on the Neues Museum with the many, many people involved. It is difficult to imagine a better compliment for what was in truth at times a bitter debate over this building project in particular, and over the approach to historical heritage in general. It is, like all compliments, perhaps too flattering. If we take it with a pinch of salt, however, it proves to have an honest core that architecture would benefit from considering. To paraphrase Chipperfield’s words, it is not primarily about buildings but about attitudes towards life. It is about the role that architecture can play therein.

By Bernhard Schulz

David Chipperfield Architects (2013)