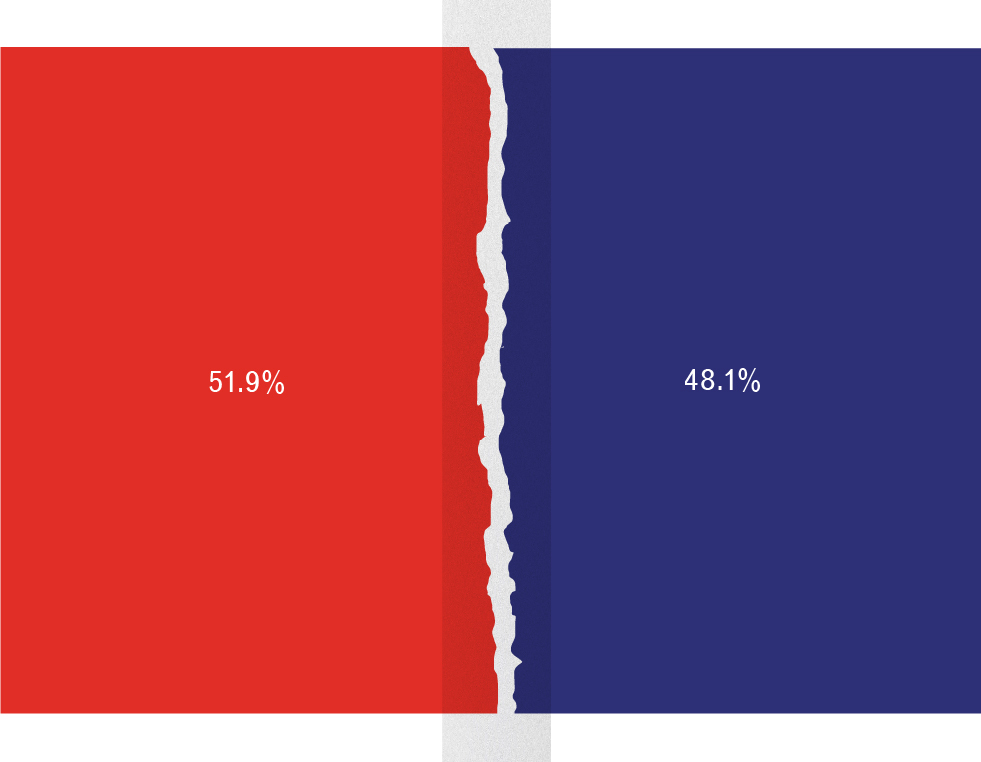

Last month a major competition was announced by the European Commission. Within the competition regulations, referring to Brexit, it warns British candidates that depending on the outcome of the negotiations ‘tenderers from the UK could be rejected from the procurement procedure’. The reality of Brexit is no longer around the corner, it has arrived.

Last month a major competition was announced by the European Commission. Within the competition regulations, referring to Brexit, it warns British candidates that depending on the outcome of the negotiations, ‘tenderers from the UK could be rejected from the procurement procedure’. The reality of Brexit is no longer around the corner; it has arrived.

Despite this, the profession – and the RIBA in particular – has hardly stuck its head above the parapet. Apart from a recent survey of attitudes to our post-Brexit future and a few platitudes asking for reassurance, there has been little reaction from the RIBA, which is surprising given that architects still believe our role involves a profound engagement with societal issues. Can we imagine previous generations of architects being so quiet about an issue that will have such an important role in defining our future and what type of society we want?

While others from the creative and cultural sectors – artists, poets, writers, dancers and filmmakers – might share our concerns about Brexit, they don’t have the advantage of a representative professional body as we do. Why are we so quiet about a process that will change our view of the world?

What is more worrying than the commercial consequences is that no one has been able to turn this decision into a vision. Brexit justifies itself only as not being something: not being subservient to Brussels, not accepting immigration and, most importantly, not sharing the regulations and standards imposed by others. We have not yet heard what we do want once we have discarded what we do not want. More importantly, those that are leading us into the fog have not been sufficiently challenged. This must be our responsibility; the failure for not doing so is not forcing answers.

A few months ago, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier asked what sort of society Britain wanted to be. Do we want to stay connected to the social-democratic tendencies of Europe or do we want to continue our Anglo-Saxon procession into deeper deregulation? The ideological masterminds of Brexit are motivated by the vision of increased deregulation, regarded as the enemy of enterprise. However unconvinced we Brits are about European habits, it is not so easy to openly lobby for deregulation and a lowering of standards and workplace protections.

Why is no one answering Barnier? If we want a new future that is not just a rejection of what we have, what is it? We should by now realise that this is not going to be delivered by the obscenely transactional politicians blindly leading us forward into an unknown future.

Is this not our challenge? Should we not all speak up and hold their feet to the fire? If we do not do it now, then when? As architects, we are on the very front line of so many of the issues that will, and do, affect us all. Should we not demand realistic answers to the issues that will determine our future, not only commercially but morally, emotionally, societally?

A healthy architectural culture depends on good education, good workplace protections, professional safeguards, cultural transfer and ambitious professional expectations. These topics require energetic demands and proposals beyond purely commercial considerations.

What is the situation of foreign nationals who work in so many of our offices? Are we not in the position to demand clarity about cultural interchange, education and research, and programmes such as the Erasmus student exchange? Will we be eligible to participate in European competitions? What will be the consequences on building regulation quality and safety standards? What about employees’ safeguards?

Of course, we know the government has no convincing answers, and there is a degree of futility in even asking, but it is more dangerous not to demand, not to make a clear representation, not to make our opinions and our concerns explicit and precise.

When Boris Johnson proudly announces that, in his new world vision, the UK’s services – and design in particular – are our great exports, can we not hold him to task and demand how, in a more culturally isolated and an increasingly market-led global economy, he thinks design and education are going to be protected, encouraged and developed? I have not witnessed any support, encouragement or help from our government.

Where is the evidence that surrendering close relationships with our nearest makes us more worldly? Surely we, as architects and planners, understand better than most the developing challenges of our times. We know better than anyone that issues of sustainability, transport, energy, intelligent use of resources, the role of proactive planning, the increasing awareness regarding quality of life – rather than only the growth of the market – are those that will define our future and that of our children. Who in their right mind can argue that workplace rights, common environmental standards, shared sustainability targets, monitored competition procedures and consideration for the longer-term social components of society are not critical to our professional environment and purpose?

An unfettered private system does not instinctively take care of these issues. The problems of privatisation, of public-private partnerships created by an emaciated public system, and an underfunded and disrespected planning system are played out in front of our eyes. How can we possibly allow the ideologues of the Conservative Party to continue down this route?

We must unfortunately admit that the attitudes that have tended to dominate the RIBA over the last 20 years mirror quite uncomfortably the orthodoxy of the market-driven system. This mentality has confused the concerns of architecture and planning with the commercial necessity to make architecture more accessible and friendly to the market. By overestimating its role as a marketing agency, the RIBA has neglected to safeguard the professional conditions that we need and should expect. The route to good architecture is not found only by marketing, but also by protecting the professional environment within which we operate.