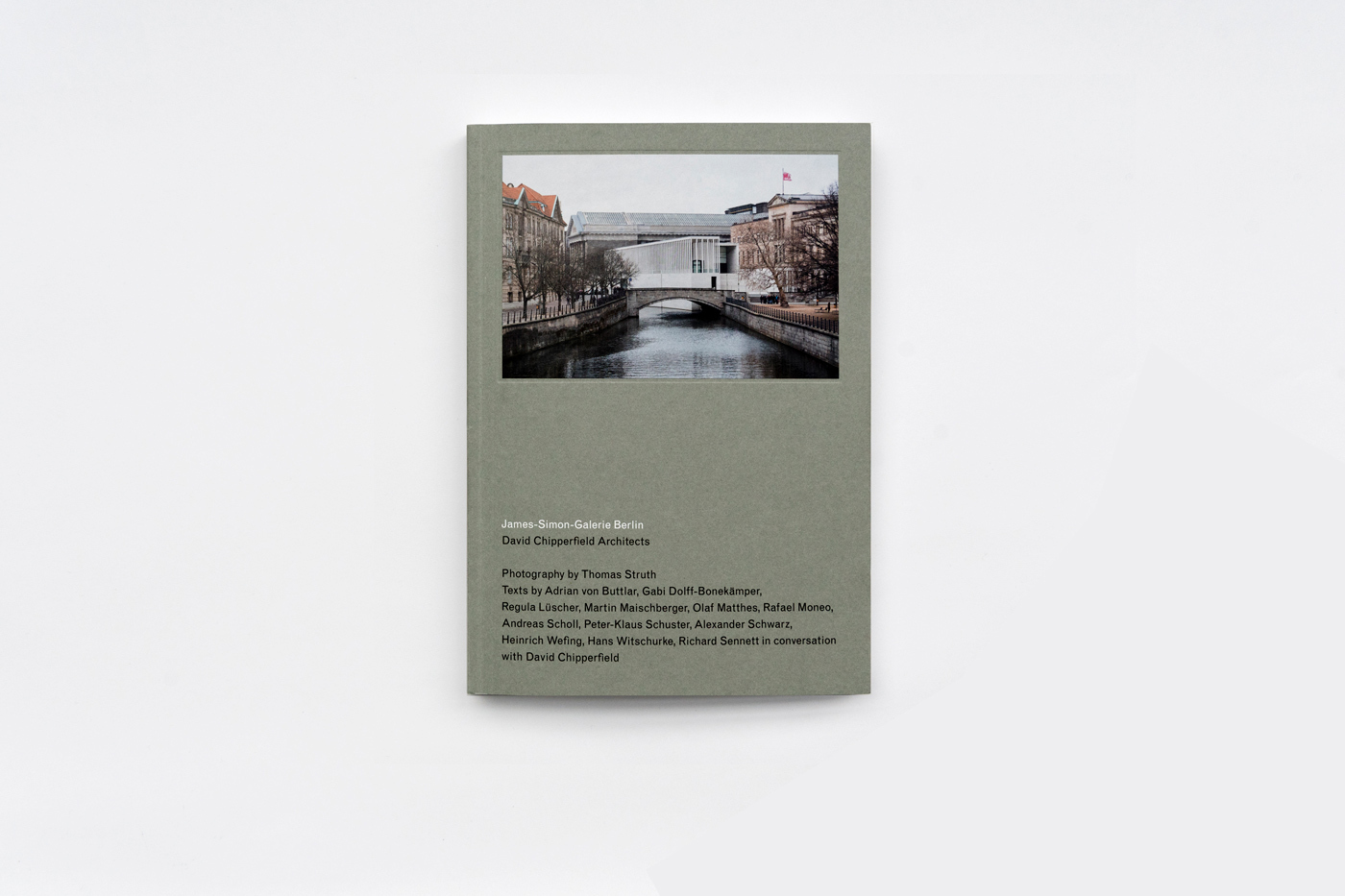

Friedrich Wilhelm IV described his vision for Berlinâs Museum Island as a âcultural acropolisâ; a sacred sanctuary for the arts and sciences that would cement the Prussian capital as the Athens of the north. Almost two centuries later, his classical aspirations have been fulfilled by British architect David Chipperfield, in the form of a dazzling white temple. Opening this weekend, after 20 years of planning, the James Simon Gallery stands as a âŹ134m (ÂŁ120m) Parthenon-on-Spree, forming a handsome new entrance to one of the worldâs most important repositories of cultural treasures.

âWe were quite nervous,â says Chipperfield, standing in the lofty new ticketing lobby, where stripes of sunlight flood in between the row of slender white columns outside. âThe challenge was how to create something that was of its context and also of our time, in this incredibly sensitive location.â

He had good reason to be anxious. His first design, unveiled in 2006, was slammed by German critics as grossly misjudged for the UNESCO world heritage site. The jumbled cluster of glass boxes was likened to âa glorified public toiletâ by one prominent journalist, in a tirade published under the headline âNot like that, Mr Chipperfield!â

The 65-year-old architect is no stranger to Berlinâs culture of fiery public debate. He worked for more than a decade to realise the acclaimed transformation of the Neues Museum, and is now engaged in refurbishing Mies van Der Roheâs Neue Nationalgalerie, a holy of holies among architects. âItâs refreshing that architecture is subject to such robust debate here,â he says, lamenting what he sees as a lack of serious public discussion around the built environment in the UK. âThey really hold your feet to the fire, which is painful at the time, but the work is better for it.â

His team went back to the drawing board and took classical cues from the neighbours, taking a lead from the broad entrance staircase of Friedrich Schinkelâs Altes Museum, as well as Friedrich August StĂźlerâs unifying colonnade, and the weighty stone plinth of the Pergamon Museum next door. These elements have been deftly synthesised into a structure that is entirely its own, a kind of stripped-back, etiolated classicism that is at once imposing and delicate. The result is a strangely scaleless structure that appears monumental from some angles, dinky from others, with its real purpose hidden below ground.

Named after one of the most prolific 19th-century Jewish donors to the museumsâ collections (a gesture intended to recognise the many other such donors who were erased from history in the Nazi era), the building provides space for the practical functions that didnât fit in the surrounding museums. It was a lengthy shopping list: ticketing, loos, cloakrooms, shop, cafe, auditorium and gallery for temporary exhibitions, some of which feel a bit squeezed into the narrow site.

Chipperfield describes it pragmatically as âa sort of subway stationâ, serving as a central entrance hub with underground connections to the surrounding buildings. A tunnel now leads to the Neues Museum, and a big portal goes straight to the Pergamon, although the other links are a task for future generations.

Anxious that it might be seen as a âdustbin of uses that didnât fit elsewhere,â the architects have endowed their building with grandiosity in bucketloads: entering this functional underworld is more akin to ascending to a realm of the gods. A broad staircase leads up in three flights to a kind of temple mount, an elevated plateau where ticket desks and a cafe spill out on to a terrace overlooking the Kupfergraben canal. Chipperfield describes it as a âpurposefully purposeless spaceâ, a civic deck where people can come and take in the view for free and stroll between the surreally skinny columns â a line of 70 white concrete matchsticks that stand almost nine metres high but less than 30cm thick.

They are a striking sight, glimpsed at the end of views down the canal, but marching rows of thin, square columns conjure uncomfortable allusions here in Germany. The long colonnade has inescapable echoes of the work of Nazi architect Albert Speer, particularly his rally grounds in Nuremberg. âWeâve been called fascist in the past,â Chipperfield says, referring to the controversy surrounding his Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach, built in 2006, which also featured decidedly Speerian pillars. âGermans werenât allowed to use columns after the war because they were so tainted by association. Being an English architect gave [my client] some relief â âWell, if he says we can do it, then itâs OK.â Weâve tried to use the language in a very neutral, minimal way.â

Inside, there is a sophistication in the use of materials that Speer could only dream of. A huge wall of translucent white marble, just 6mm thick, casts a pale milky light into the entrance hall, while a perforated copper ceiling shimmers overhead. Steps lead down to a level of cloakrooms and loos, designed as a warm wooden world lined with book-matched walnut veneer â great tree-trunks thinly sliced and opened like the pages of a book, so the grain forms mirrored Rorschach patterns as it wraps around the walls.

âWe wanted the buildingâs concrete structure to be exposed, then lined with richly decorated surfaces formed by nature,â says Alexander Schwarz, design director of Chipperfieldâs office in Berlin, a violin-maker-turned-architect whose attention to material detail oozes from every corner of the project. The 300-seat auditorium is a mini masterpiece, with concrete walls cast in pleated acoustic folds, and a ceiling that plunges down in three dark wooden waves like draped fabric. Elsewhere, wafer-thin steel benches are upholstered in pale leather, while dark patinated bronze brings a weighty touch to the doors (quite literally â theyâre incredibly heavy to open).

It all sings with the seductive Chipperfield brand of restrained opulence, but there is a slight sense throughout the building that architectural gesture sometimes overruled practical function. The circulation spaces are expansive, but the new 600 sq metre gallery for temporary shows feels a bit shoehorned into a corner, uncomfortably long and narrow. Meanwhile, a charming staircase leads down to the water along the canal-facing facade, suggesting the romantic Venetian possibility of arrival by boat, but sadly it is nothing of the sort: no boats will be permitted to stop here. âItâs an affectation,â Chipperfield admits. âA human gesture to suggest the building dipping its toe in the water.â With a vocal campaign underway to see this stretch of the waterway transformed into a public swimming area, it could be the perfect place for bathers to pad up the steps to sunbathe on the terrace â a suggestion that makes the museum directors tremble at the thought of people arriving at their sacred cultural citadel in dripping trunks.

Which is a shame, because it could do with a touch of Berlinâs more bohemian, freewheeling spirit. It is an elegant and supremely well crafted building, but it feels a bit chilly, parked on the waterâs edge like a superyacht. With luck, the swimmers will get their way, and the gleaming acropolis will live up to its intention of being a truly welcoming civic space.